My Life in the Labor Movement

We moved around a lot when I was a kid, people always asked if my Dad was in the army. No, he was a construction superintendent for S S Kresge, later to become Kmart. He was born in Winnipeg in 1914. The family was large and poor, a poverty that sat heavily on an unhappy family and was close to an obsession for all of them. Aunt Sonya's stories at 75 sounded like they had happened the day before and it was like that with Dad. Grandma was a strait-laced Irish lady, grandpa an illerate elevator operator at the train station. I remember visiting her in Los Angeles when I was thirteen or so. I'm named after her revered brother, who died young, and she sat me down and told me never to forget that I'm Irish (I'm 25% Irish). They say the Nazis are bad, but they're nothing compared to the British, who oppressed us for hundreds of years. Brash even at that age, I wasn't so stupid as to utter a word of opposition. The girls were to start in show business in order to meet wealthy men and find one to marry; the boys' path was education. The girls left home in their teens and became show girls (I've got pictures!). Uncle Wally got a PhD, but Dad was on the ten year plan for an engineering degree at the University of Manitoba. Grandpa beat the boys and Dad knocked him down once when he was starting in on Uncle Ed, said I'll kill you next time. So that was the end of life at home and up to the gold mines at 14, the Rio Grande Mine in northern Manitoba.

Dad would regale us with stories of the One Big Union, a syndicalist IWW type outfit in Canada. Big on free speech and workers' power, weak on organization. I got the impression that Dad depended for personal support and safety on their little cell in this remote, tough, nearly all-male environment, where rape and other forms of violence were not unheard of. The boss was less problem than scabs and psychopaths among the workers. They would put thick metal plates on the floor of a tunnel being mined, then dynamite the walls and shovel the rock into rail cars that were driven in. They used short stoping shovels for that and they were used for self-defense as well as for mining purposes. Like the IWW, OBU members had a red membership card to recognize each other. They telegraphed OBU HQ in Winnipeg once when they really needed some help and the telegram came back that they had no one to send, the men needed to use the power of the little red card to defend themselves. The boys felt that left something to be desired.

We were raised Catholic (try explaining anything else to grandma) and I attended seven Catholic grade schools in different cities, then Jesuit High in Dallas and South Catholic in Pittsburgh (1961-65). I was an altar boy for eight years. There was a strong component of social justice teaching throughout (especially in high school) and my wife Rose Marie reports the same for the Chicago Catholic schools she came up in. That had an effect, but there is the organizational aspect as well - you are used to being in a large organization and understanding its efficacy, even if disagreeing on particular points. After graduate school in Madison, we had a little worker collective that put out a newspaper we hawked at plant gates, We the People. We never talked or thought much about religion, but one day it came up and all but one person was raised Catholic or Jewish - that struck me.

Dad was a visceral pacifist. There was the Irish nationalist connection, but I think that in his own life he had seen more than enough violence and had no illusions about how devastating it was. He would talk about how he dodged the draft in Canada during World War II (home guard only, but not getting close), how working in war plants made him the man behind the man behind the gun. Uncle Ed had been drafted by the American Army as a resident Canadian in the US and went through hell as a signalman in Europe. One of his stories was retiring in disgust from his associates' stripping a column of German prisoners of their personal possessions - down to a wine cellar and oblivion, resurfacing later to a scene of mass carnage, all of them. Mom too; third and fourth cousins on her side talking about the flight from Prussian militarism in terms identical to those I'd heard from her. Her father's father had been murdered in Iowa on his own property line in 1883 and her father could not abide guns, even when nearly alone on the plains of Saskatchewan, the nearest neighbor a speck in the distance. Later in life, I told her that I wasn't going to be going to Vietnam back in those days. She said everyone just assumed that, that I'd go to the relatives in Canada if necessary. Henry Kissinger spoke at my commencement at Pitt in 1969. Many of us regarded him as an arch war criminal and I wasn't going to attend, as important as education was to me and Mom and Dad. So she says, "Michael, you know I don't ask much ...". That is an argument you are going to lose - sorry for being such a dick, Mom. If I remember, we turned our backs on Kissinger during the ceremony. My draft board in Pittsburgh took graduate school as worthy of a deferment, the department telling them how valuable I was to the war effort. Then I got a number in the 300s in the draft lottery, well beyond birthdays that would be called up.

I worked industrial blue collar jobs in the summers through undergraduate school - some union, some not, but sufficient to pay tuition and books at the University of Pittsburgh (1965-69). The civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements were pushing me leftward and I "lost my faith" as the Catholics would say. I attended the anti-war protests around the Democratic Convention in the summer of 1968 in Chicago and was busted in Lincoln Park, where I'd flown kites with Dad as a little boy before the family struck out on our hegira. In early 1969, just as I was considering graduate school, there was a picture in our local newspaper showing what looked like tens of thousands of student strikers in Madison, Wisconsin - the black strike. That piqued my interest, let's apply there! Which I did and was accepted as a graduate student and teaching assistant in the Math Department, the TAship sealing the deal.

The Teaching Assistants Association had been organizing graduate students and took off a year or two before when mossbacks in the legislature threatened to discontinue tuition remission. That is where TAs have their graduate school tuition reduced to in-state levels, a considerable benefit enabling out-of-staters like me to finance graduate school. Anti-Vietnam War considerations were also important, many TAs not liking the prospect of having to fail students, making them fodder for the draft. Evidently the right-wingers in the legislature thought they were being swamped by commies from out of state. Which is a joke right there for anyone who knows their Wisconsin history - Fighting Bob LaFollette, the progressive movement and all the rest. I was amused later to learn that my great grandfather on Mom's side, John Hidinger, was a veteran of the Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War (the eagle regiment after mascot Old Abe). He was an Iowa boy, that's what I'd grown up with, but evidently the pacifistic family were non-too-happy about escaping militaristic Prussia in 1848 only to have their son sign up for war here. So he shot over to La Crosse with a buddy and joined what became company I of the Eighth Wisconsin, marching around Camp Randall for a few weeks before setting off to campaign with General Grant.

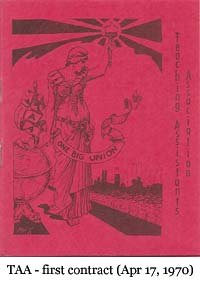

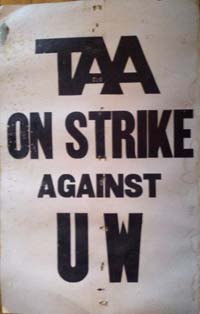

The TAA was an autonomous expression of the student-labor alliance and was unaffiliated with any larger union. In fact the larger labor movement was stand-offish. Hank Haslach, a Math Department TA and TAA leader at the time, told us he and others had gone to the Labor Temple in Madison to meet with the local AFL-CIO leader, Marv Brickson of the Painters Union, who turned them back at the door reciting the anti-communist clause of the AFL-CIO constitution. Fine with me, better to be independent. After the 1970 strike and contract, those big labor organizations came courting and the TAA affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers in the mid 1970s I think. The TAA was open to all the progressive currents swirling around campus, but was an unabashed labor organization pressing bread-and-butter issues as well. It was invigorating for someone like me and I started to get involved. I met my wife at a TAA party at the Stone Hearth Coop on January 31, 1970. We went on strike in March 1970 and Rose Marie and I picketed in front of Science Hall for three weeks or so, I still have the picket sign. The strike was illegal and four department heads surveyed classes that were supposed to be taught by TAs and turned in names of those who weren't there. I was one of them, and had to go to court and ended up paying a fine, which the union turned into a little cause célèbre and paid.

After the strike, I became the chief steward in the Math Department till leaving graduate school in May 1973. The Math Department had probably the largest corps of TAs at the University, offices all up one side of Van Vleck Hall where we were jammed in eight to a room or something. Of course that aided self-organization - we had captains on each floor and lieutenants in each room. If HQ called a meeting at 10:00 am, I'd get leaflets to the six captains and just about everyone would know by noon and we'd have a good complement of Math TAs there at 5:00 pm (hand-cranked mimeo, baby!). The contract was short; we stewards carried it with us everywhere - it had a red cover with a lady liberty figure holding a beacon of hope above the industrial masses and bedecked with a sash reading "One Big Union", printed of course by an IWW shop. Sign-up cards too, always ready; turnover was massive, so constant internal organization was the watchword. The contract called for departmental bargaining. There is a stunning lounge on the ninth floor of Van Vleck where professors and graduate students congregated, talked math, and played Go; wall-to-wall windows, both lakes, the capital, and great vistas of Madison visible depending which way you look. Department members, including TAs, had keys to the lower elevators giving access to the ninth floor. I proposed opening access to all. That was done and still in force when I took my grandkids up a few months ago to check it out.

Anti-war and union work mixed seamlessly; you'd have to tell someone quickly exactly what the demo was about, because it could be either. Of course professors divided on the war (as we did, but less so, there was definitely a generational component). They were generally liberal, but of the namby-pamby variety, as we saw it. A few vocal war-mongers too. I remember one professor, Robert E. Lee Something, explaining to me how North Vietnamese were chained to their tanks - it was all coercion with them, they didn't value human life. Kent State followed the strike in quick succession (May 1970), closing down campus again. That was a lost semester. TAA ideology held that the university itself was an integral part of the war-mongering state and culture. The Math Department had provisions for graduate students to add agenda items to their meetings, so one day in 1973 a number of us Math TAs sponsored a resolution censuring the Army Math Research Center, calling it an arm of US imperialist aggression. We got a few minutes to address it, the professors pissed to the max, rigid and stony-faced. It got a few votes in this large department and one of those hands was not held very high. He was a young guy some of the TAs knew well from New York City, where his mother was a labor and anti-war activist, and she was going to be told in case of a bad vote. I can see it now, the other mother saying, "Rachel, I understand your son the mathematician voted for US imperialism in Madison". Much later, my daughter Eve had that professor for Calculus 221 (which I had TAed for), she liked his quirky humor.

Looking back, the TAA was a highly productive labor organization. Of course we turned back the tuition remission threat, won the strike, and got a contract. That's under the heading of basic worker self-organization and protection. But there was a lot of education going on too, and not just in the classroom. The professors didn't like the TAA one bit; one told me he resented that we had separate parties - not like in the old days when everybody partied together. I understood his point; the great subtext of graduate school is induction into the profession, serving an apprenticeship. We pulled in a different direction, emphasizing TAs as workers rather than supine apprentices. The Math Department was a TAA hotbead; on occasion there would be contentious meetings with the department chair, a professor who had rotated in, but was our boss too; it's a miracle so many of our activists ended up as math professors, considering all of that. Professors would snarl at us on occasion that they'd stop having TAs one of these days, we were making so much trouble. We'd laugh at them - go for it! TAs taught the great majority of small undergraduate classes; plus, the TAships helped fund graduate students who populated all those graduate courses so dear to our professors.

We were educating ourselves as union activists and it took in many ways large and small. The TAA developed and sent out entire cohorts of labor leaders. One was Bob Muhlenkamp, our president during the strike. Bob was a rousing speaker and a great leader. The 21 of us who had been sued during the strike formed a subcommittee to deal with our situation. I remember one meeting at the old Brooks Street office. One of us was running the meeting and Bob was off to the side working on some papers or something. He didn't say a word, but I knew he was listening, because he'd smile now and then apparently in assent to something that had been said. It struck me - such a dynamic leader, but he'd rather have us handle it by ourselves. That is leadership development, that is democratic practice. Bob went on to hold many important positions in the labor movement, including organizing director of the Teamsters in Washington, and was a cofounder of U. S. Labor Against the War in the 1990s.

Jim Marketti was another TAA leader. During the 1970 strike, Jim did liaison with Teamsters Local 695. Their members drove the buses between campus and the remote parking lots (Lot 60), so it was materially and morally important that we have their support, that those drivers not cross our picket lines. And have it we did, Jim making a good impression on Don Eaton, the Secretary Treasurer of Local 695. In fact, Jim went to work for Local 695 as an organizer after the strike, participating in their extensive organizing drive throughout their jurisdiction in south central Wisconsin, which increased their membership from about 4,500 to 5,500 in the early 1970s. Jim was the very image of a hard-nosed, old fashioned working class militant for many of us, but one of us too. Jim insisted relentlessly that worker organizations were only as good as their members, that participation was not an extra, but the heart-and-soul of the labor movement - participatory democracy, a message very much in the air in the youth movement of the 60s and 70s, but now embodied in our very own union leader. It was thrilling to hear him report to our general meetings before and during the strike about working with the Teamsters. When a Teamster himself, Jim sponsored an anti-Vietnam war resolution at Teamsters Joint Council 39, the group of all Wisconsin Teamster locals. I believe it passed too, but not to everyone's delight, foreshadowing the clash of civilizations to follow in Local 695. Jim went on to a career in the labor movement and ended up in the CWA.

I started losing interest in graduate school in 1973 and quit in May that year. A friend was about to quit his job as a laundry driver in July and said why don't you come along on the route my last few days. I did and then went in the day after he quit at start time and asked the boss for the job, said I was ready to start that moment. The boss was Sid Sweet; he had recently bought Quality Laundry and moved his operation to their plant on Regent Street. Quality had had a union, but he busted it. After a few months, I started organizing the workers, starting with the drivers. We went to Local 695 in March 1974 and Business Rep Tom Kiesgen gave us cards to distribute. Everyone signed, or close (seven of us). The inside workers gave it a shot as well with the Laundry Workers Union. We drivers won our representation election 8-1 (I wonder who the boss's son voted for), but the inside workers lost theirs. Sweet had threatened to close the plant if the union came in, which he ended up doing anyway in September, stiffing his hotshot anti-labor attorney, among others. Our paychecks bounced.

Around the same time, Local 695 was put into trusteeship by the International just before a key local election (November 2, 1973). A faction led by ex-Secretary Treasurer Al Mueller led the charge, in league with the Capital Times. Mueller had been a mentor to Don Eaton, but was pushed out and evidently felt that Marketti was to blame, as well as Eaton. Mueller and the paper deplored some rough organizing strikes, also the pooling of strike benefits. According to the IBT, individual strikers get benefits from the International when involved more-or-less full time in a strike. It didn't amount to much, so the local would apply for benefits for some strikers who had gotten other jobs, then distribute those extra benefits to active strikers. It was a common practice in the IBT, but a violation, and Mueller and his people complained bitterly about it and had those complaints amplified by the Capital Times.

Local 695 was a general local covering a great swath of southern Wisconsin; the number 695 had been attached to Mueller's old local in Watertown, which had merged with 442 in Madison and the Richland Center local to form the new Local 695 based in Madison. Mueller was a hard-driving union man who had spent a lifetime building up the local; he was an autocrat who identified himself completely with the local and took it very hard when pushed out (after installing Eaton as Secretary Treasurer, he occupied various formal and informal positions of trust in the local). I remember Mueller talking animatedly during our later campaigns about how bracing it had been as a young man travelling alone to some remote crossroads to bargain with hard-bitten farmers on a coop board for their four workers. In the early 70s, Mueller still had a large following in the local, especially in shops he had worked with.

Food processing operations constituted maybe half of Local 695's membership - there were four Carnation plants in the jurisdiction, for example, and any number of canneries, cheese plants, milk plants and the like scattered through rural areas like in Dodge County. There were a number of police also, mostly sloughed off early in the trusteeship (all the decertifications during the trusteeship was one of our campaign issues). There were some large shops, one of the biggest being the bus company in Madison where some of our activists worked, but probably the majority of members worked in shops with fewer than twenty people.

The IBT was the largest union in the country after the NEA and took in all kinds of workers. The constitution claimed jurisdiction over drivers, chauffeurs, warehousemen, cannery workers ... many others enumerated ... and all other workers. Expulsion from the AFL-CIO actually helped them in the field, freed from anti-raiding constraints imposed by the federation. In polite society, Jimmy Hoffa was a hood, but many workers admired him and thought of the Teamsters as exactly the kind of kick-ass outfit needed to deal with intransigent employers.

Back in Local 695, Marketti was fired immediately - the trustees from Milwaukee Local 200 liked him no more than Mueller did. Jim immediately started a group to oppose the trusteeship, Teamsters for Democracy (based on Miners for Democracy, which was involved in taking back that admired old union from crooks and murderers). He started a newsletter, filed a suit in federal court against the trusteeship, and stared agitating throughout the local. There was a three-way local election in December 1974, won by trustee-installed Bob Rutland as Secretary Treasurer. Secretary Treasurer was the main executive office and more important by far than the rest of the Executive Board (two other full-timers and four part-timers).

I'd gotten a job as a beer and liquor driver at Simon Brothers in October 1974 and was not involved in all this. We were housed in an even-then decrepit old building at East Washington and Paterson in Madison. Simon Brothers was unusual in mixing beer and spirits on straight trucks. We worked four ten-hour days and I was out of practice. It didn't take long to develop callouses and I only fell asleep in the bath tub after work a few times. Marketti had organized Simon Brothers shortly before in the wake of the bitter General Beverage strike (I had done a little activist work in front of liquor stores for that one). I helped organize some meetings of the liquor drivers from all the companies and advocated for an industry-wide contract. In November 1976, Simon Brothers was sold to General Beverage, who then fired most of us in December. Much of their business was "pirated" (according to GB) by Edison Liquor, a Milwaukee outfit who set up shop in Madison.

A co-worker who wasn't pulling his weight was known as a "leaker" - more literally, a bottle with a leaking crack. You really hated leakers out on the route (leaking bottles), because they could ruin a whole case. Sometimes you couldn't tell which bottle was leaking, you'd set the case at the back of the truck and then short a customer, amend the invoice, and on and on, what a mess. And you really hated co-workers who were leakers too, they had all the features of a real leaker. That was the ultimate insult, to call someone a leaker, and an invitation to violence if you said it to their face. I suppose the usage came out of the beverage industry in Milwaukee, but working class people in Madison used it widely. It was kind of ingrained, but people outside that world didn't get it, so I stopped saying it. And too bad, what a descriptive term - "Guy's a leaker, man!".

Edison hired me and I drove for them until being fired, ostensibly for an accident in early August 1977. That was shortly after my daughter Lydia was born. They say being fired can be one of those big personal hits, and that's how it is was for me. The boss had waited three weeks; that looked suspicious and they even told me it had been cleared with the union. I had been active within that little shop and had gained an increasing profile as a TFD activist, appearing in the newspaper. So I filed an unfair labor practice with the NLRB on my own behalf and bothered all my friends who were union reps for advice. The NLRB filed a complaint on my behalf (far from a foregone conclusion in such situations). The kicker might have been when one of the bosses threatened me for filing the ULP - that instantly became an amendment to the complaint. Workers' individual rights are one thing, but challenging the majesty of the NLRB, by God, that will not stand. As this was proceeding, I had gotten another job, so waived reinstatement and accepted full back pay to settle.

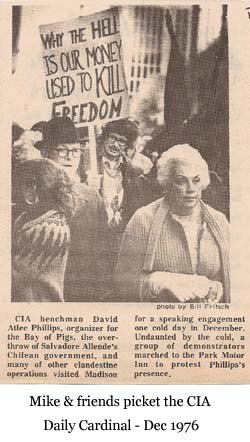

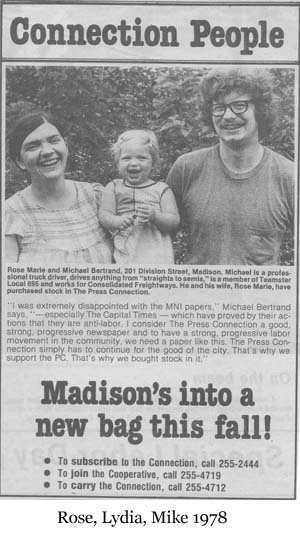

I was active in the broad progressive and labor movement in Madison throughout this period and had a lot of company. Dave Newby, labor liaison for the TAA in the mid 70s, was part of a progressive bloc at the Madison Federation of Labor, the AFL-CIO central body in the Madison area (now the South Central Federation of Labor). He replaced Brickson as president and went on to become president of the Wisconsin AFL-CIO for many years. I joined student groups to protest CIA operative David Atlee Phillips when he spoke to the Madison Civics Club at a downtown hotel in December 1976. Surprisingly, we walked right in and lined the corridors, chanting anti-war slogans. We could actually hear this numbskull speaking - oh the hijinks I have done, what a big lark it was overthrowing Allende and the like, as if it were play blood. At a couple points, we started chanting "Bullshit!" and they could hear us too. Short years before it would've been, "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh - the NLF is gonna to win! Ho Chi Minh, Madame Binh - the NLF is gonna win!" Welcome to Madison. When Madison newspaper workers went on strike in 1977, I was on the board of their daily strike paper, the Press Connection, and learned something of that business. I rented a 45-footer one Saturday to go up midstate and haul down some rolls of newsprint for them. It had a sleeper and high cab which enthralled my daughter Lydia when I took her out for a short spin before returning the truck.

I became active in TFD starting in 1975 and worked on the newsletter committee, as I had in the TAA. Marketti had been concerned that the sharks in the Wisconsin Teamsters movement wanted to carve up Local 695 and that didn't seem to be happening, quite possibly because Jim had loudly raised the alarm. Jim and other early TFD activists were furious with Mueller for delivering the local to the International and in particular to their local Wisconsin representatives in Milwaukee, both of whom Mueller himself had fought bitterly over the years. We put out a newsletter through 1976 and early 1977, until the next officers' election loomed in December 1977. Dodge County was my route (I had Mondays off with Simon Brothers and worked nights sometimes in my new job); coops, redi-mix and construction operations, cheese plants, canneries, police departments - that gives an idea. We'd just walk into places on our list and try to find the break room, ask if we had to (front desk for police departments though). That was natural for delivery drivers, part of the job. But still. Union reps do things like that all the time, especially in the course of organizing a new shop. But us? No institutional association or protection whatsoever. Anyway, we delivered a lot of newsletters and it was habit when elections came around and time to deliver literature promoting candidates.

The local was broken into three factions of roughly equal sizes - Rutland, TFD, and the Mueller group. Inside TFD, I advocated a fusion ticket with Mueller and his group. Marketti had left Madison for other labor jobs and TFD's main leader was John August, who had had various jobs in the jurisdiction (Yellow Cab, General Beverage, Madison bus company). We met with Mueller and associates to put a slate together, but August reneged a few days later under pressure from his wife Phyllis Perna, another TFD activist. They disinvited me and others from meetings putting together an all-TFD slate, until I insisted on being included. Of course Mueller and his group did the same, with Motor Transport driver Roger Witz at the top of their slate. So there were three different slates and Rutland squeaked in again in December 1977 (Rutland 964, Witz 789, TFD's Machkovitz 699).

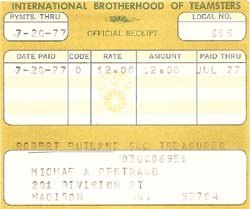

I'd become increasingly involved with the national dissident group Teamsters for a Democratic Union. They started in 1975 as Teamsters for a Decent Contract (National Master Freight Agreement) and a number of us from Madison went to the founding convention in September 1977 and I ended up on the first steering committee. I thought it was a valiant effort, but something of a mismatch for Local 695, considering the freight-centric emphasis of TDU. Oddly enough, I'd gotten a job at Consolidated Freightways in the fall of 1977. Our terminal was on Pennsylvania Avenue near Third Street in Madison - on the north side near Hooper, later moving across the street to the larger Motor Transport terminal when they folded. A tip of the hat to my terminal manager Jim Scharping, a large-minded person who seemed to think it might be interesting to have someone like me around, in spite of so many differences of background. Start on the dock, then hostling in the yard as time goes on. No better practice than repeatedly backing semis up to the dock in our atrociously pitted yard - somehow the farm boys found backing up trailers a lot easier than someone like me. Then spotting a 45-footer at dawn one morning at Sub-Zero, first time on the actual street; I think there was only one stop sign negatively affected (the back wheels don't follow the front wheels around a corner, hey). Next thing you know I was out on a day route: in at 7:00 am and finish loading the trucks with inbound freight, breakfast maybe with a couple of the boys, hit the route with deliveries, then call dispatch for outbound freight to be picked up at 1:00 pm or so. Back at the dock later in the day, finish loading outbound trailers and put them in the yard for the over-the-road contingent to get every night as they drop off inbound trailers from our hub in the Chicago area. Our Teamsters business rep came in one day I happened to be in the office, Dave Shipley. I actually didn't hate this guy even though he came in with and was a friend of Rutland. He was a fighter, an attractive quality for us Teamsters, even though we were sometimes the target of his wrath. I was wearing a stupid sock hat with a big bob on the top, fresh in off the dock. Shipley started teasing me about it and I said "Go f*ck yourself" with some energy before storming off. Jim Scharping smiled (so did Shipley); he wasn't going to be firing me on Shipley's say-so. "Mikey blew a gasket", one of the boys said. That was my name, like Johnny, Wolfie, Bobby, and the rest, just like the old days at home.

Rutland himself struck me as a soulless apparatchik - an unfair appraisal no doubt, considering all we put him through. The local was not dismembered as we had feared and was returned to local control, though a satellite of Local 200 for some time, so different from its independent origins. I just ran Local 695's LM-2 online, which showed 5,191 members in 2012, compared to the 5,500 or so Eaton bequeathed them in 1973. Just treading water, but not nothing considering the anti-labor offensive of the last forty years. Still, these figures highlight the dynamism of the Eaton era, which added 1,000 members in one intense organizing drive in the early 1970s before being stopped by the International. Those LM-2 forms unions have to fill out for the Department of Labor were harder to get in the 1970s; it was by mail. That was one of my duties (the research department); also to get data on all the decertifications in Rutland's early years - ostensibly public information, but taking some spade work to get from the NLRB, WERC, or other agencies. We hammered Rutland with those decerts and put them in the newsletter and campaign literature.

I made the mistake of distributing some TDU literature at the labor Temple at a freight ratification meeting in April 1979 - the mistake was doing it without some associates. A number of C C Riders were Teamsters, including in freight, and they were always helpful in such situations. TDU advocated voting no on the national agreement and that infuriated our local officials; you wonder the ramifications if they turned in "bad" numbers to HQ. So Shipley confronts me and starts jostling to get the leaflets. To quote from my report at the time:

Then Shipley lunged for the leaflets and grabbed them. I held on and struggled for possession. Then Shipley hit me in the face, knocking off my glasses and breaking them. The leaflets fell to the ground and I started to defend myself. Renz (President of Local 695) stepped in between us and said to me, if you're going to fight anyone, it's going to be me and I'm warning you, I'm an expert in judo and karate. I said, if you hit me first, I'll fight you for sure. He said, I'm not that stupid. Shipley took off his tie and said something to the effect of "let me at him". A loud, nose-to nose argument continued vehemently for several more minutes between the three of us. ...

At the start of the meeting, I stood up, said what had happened, and asked Rutland if it was Local 695 policy to assault members for distributing literature. Rutland said he knew nothing about it and handed the chair over to Renz. A shouting match ensued between the two of us, the Sargent-at-Arms was called, and it seemed prudent to sit down and shut up at that point. This incident made the news and I got a call from a Teamster friend who knew Renz and how rough he could be. He said he'd heard I was worked over pretty good, like I'd been held and punched repeatedly in the kidneys or something. I laughed and assured him it was nothing like that, not to worry. So I did Bill Renz a good turn that day, because there are people a whole lot tougher and better motivated (there always are!) who would have been glad to have a chat with him about it. That ended up being the FBI, sent around by the US Attorney I complained to after getting menaced on the route by Renz's boys ("wait till those biker boys aren't around, pal, you'll get yours"). I scheduled a meeting with him and asked him to enforce federal law preventing this kind of thing (the Landrum Griffin Act). I'll never forget this, the guy says we have prosecutorial discretion, we don't have to act on every violation. I was starting to get concerned that it was open season on me, so looked him straight in face and asked deliberately exactly what it would take - a broken arm, ruptured organs, what? I'm serious, what would it take? Is someone going to talk to my wife and daughter afterwards, is that going to be you? I was just starting too before the guy says, Ok, we'll send the FBI around. It was weird, because as a sixties survivor, the FBI was not my idea of a great protector, but it seemed to help in this case.

In 1979 we started thinking seriously in TFD about the next Local 695 election scheduled for December 1980. I continued to push for fusion with the Mueller group, fueled by the debacle of 1977. We had many meetings together and had to think about the slate, Secretary-Treasurer being critical. I and others encouraged August to run, but he declined and said he was going to be moving. We came up with a joint slate, but a few days later August again told me he couldn't support this after all, he'd lost enthusiasm for the ticket, blah, blah. It was a phone call and I could hear Perna screaming in the background. I said what, momma doesn't approve? He said he resented that. I laughed and said we weren't doing this again, we're going ahead with the fusion ticked as planned. August continued on to a career in the labor movement, ending up working as a apparatchik for the SEIU in California after the International put their rank-and-file oriented, kick-ass California health local (SEIU-UHW) into trusteeship in January 2009 on trumped up charges. That trusteeship made the one over Local 695 look benign; leaders and workers broke off to form the National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW) and continue the valiant fight for rank-and-file unionism. Andy Stern, then SEIU chief and arch dictator, said they were undemocratic, you can't make this stuff up.

Proceed we did, Roger Witz at the top of the ticket. I was candidate for vice president, a part-time (non-staff) position. I put everything I had into it and reviewing the campaign after all these years, there was a lot to do - publicity (newsletter / election literature / press contact), liaison with Rutland to mail our campaign material, continual outreach to members, legal, finance, policy formation, security, and research. But we all had jobs too. The officers and business reps of Local 695 campaigned as a matter of course; even if scrupulous, their very presence in workplaces, contractually guaranteed, provided access we did not have. Our literature was thrown out by employers, who claimed rigorous impartiality, but of course that works against the insurgents. We got suspicious when so many employers used virtually identical disclaimers and filed unfair labor practices with the NLRB against a couple of them for prohibiting our literature in break rooms and the like. We won against Carnation in Jefferson, where we had quality contacts. The employer had to post an NLRB notice saying they wouldn't interfere like that in the future, but cold comfort in 1982.

Local officials have many angles for influence in an election like this, and Rutland used them all. The local constitution specified that candidates for office have to have two years of continuous membership before standing for office. It seems reasonable, but has the effect of ruling out many workers and makes planning a nightmare. Witness my checkered career, stable lately but a lot of bouncing around. Roger Witz's long-term employer had folded and he was scrambling throughout the pre-election period to maintain his continuous standing. We had nothing without our candidate for Secretary Treasurer, but Rutland refused to tell us if he considered Witz eligible until the last possible moment. One of his candidates for trustee got better treatment; he was a deputy sheriff in Waukesha County, which had decertified Local 695 some time before (one of many police departments to pull away from the local in that period). No problem, he paid his own dues and still eligible. Those on the other side would get a withdrawal card right away (that's exactly what happened to Marketti). We didn't even know when the ballots were going to be mailed out, which ended up being earlier than previously in local elections.

Rutland had a mailing to the entire membership about the same time the ballots were mailed red-baiting me, so we had to scramble to answer that. Of course timing is important in such a situation and our rejoinders arrived days or weeks after many members voted. Many people vouched for me and there were no recriminations in the group, maybe people figured there wouldn't have been an election in 1980, or not much of one, if it hadn't been for me. We lost in a close one (Rutland 1,480, Witz 1,390 and for VP: King 1,550, Bertrand 1,313). Apart from the natural and heavily-pressed advantages of incumbency in administering the election, I think the main factor was that we were just a bit too late. Seven years is a lifetime in local union politics and Rutland and all his business reps worked tirelessly the entire time to erode our support and enhance his. We all knew members who had been Eaton or Mueller supporters but who gravitated to Rutland over the years. We filed a protest with Joint Council 39 that the election had been unfair and had a hearing. Of course, the protest was denied, so we appealed to the International - denied again. Then to the Labor Department, denied there too. We thought there was a chance with the DOL, we'd seen other Teamster elections voided on grounds similar to ours. We would've skipped the kangaroo court inside the union, but the DOL expects you to exhaust those remedies before appealing to them. Don't even think about missing a deadline. We found out later through a Freedom of Information Act request that the Minneapolis DOL had found three violations of the LMRDA, but Washington said that they weren't going to pursue it.

Teamster politics at the top were pretty sick in those days. As mentioned, being cast out of the AFL-CIO actually helped the Teamsters in some ways, but the stigma of mob connections from the congressional hearings in the 1950s left a mark. Teamster officials acted like outcasts and tended Republican, hobnobbing with Nixon and endorsing Reagan in 1980 and even 1984, after he busted the air traffic controllers and relentlessly forwarded a reactionary agenda across the board. No doubt many a Teamster official liked the idea of getting the government out of people's business, targets that they had been. It was a little self-contained world. Rank-and-file Teamsters had their own pension funds (the notorious Central States Pension fund that I'd been enrolled in, for example), but there were additional ones for officials - higher officials might be in three or four Teamster pension funds. So being thrown out of office in a local means a greatly reduced pension and back to the plant or the truck, which is exactly what expelled Local 695 reps like Gene Machkovitz, Tom Kiesgen, and Moose Vandre did (well, Eaton went into the Federal Mediation Service). That right there would provide good incentive for someone like Bob Rutland. Teamster International President Roy Williams went to prison, replaced by FBI informer Jackie Presser, who had reportedly handed over the goods on Williams. It looked like the Justice Department had protected Presser for years, but he died as indictments against him were moving forward. These guys were so isolated that they took direction from a whack job like Lyndon LaRouche, who made a point of defending Brilab targets (Bribery - Labor, a federal initiative targeting labor racketeering). LaRouche made inroads among Teamster officials - I saw his literature at the Local 695 hall on occasion. Evidently no one else would touch them, that's a strong form of isolation.

Isolation is something I never felt in Madison, which was busy developing a burgeoning progressive movement that I was part of at every step. We felt someone like long-time Madison Mayor Paul Soglin, an anti-war and youth activist himself, had more in common with us than with an interloper like Rutland and were pretty confident there were many people in authoritative positions locally like him. I live on the near East Side of Madison, behind the Barrymore Theater on Atwood Avenue, and have since 1975. My neighbors didn't vote for Nixon, they didn't vote for Reagan. I used to joke that there are two parties on the East Side of Madison - the Democratic Party and the (considerable) group to the left of them, the two converging lately to rack up 95% totals for progressive Democratic candidates.

We tried to hang on after 1980 and put out a few newsletters under the United Teamsters banner, but the wind had gone out of our sails. My buddy Dave from graduate school taught programming at Madison Area Technical College and worked as a programmer, like so many of our peers from the Math Department. He introduced me to the Casio fx-3600p programmable calculator in 1980 or so. I touched up programs during down times on the route, it started to consume me. This was the time you could buy a Commodore 64 for a pittance, shortly thereafter an IBM PC. It was so different from the old days where a technical and corporate priesthood rigidly controlled access to their big machines. It all appealed to my anti-authoritarian side, not to mention that you had this math machine right at your fingertips, now that's fun. So I started training myself and got some articles published. That plus a Masters degree in Mathematics got me a job teaching math at MATC in August 1984, it was the job Dave left to become a full-time programmer. I knew it was close when the Vice President called me in, but was a little abashed about the interruption in the professional resume, eleven years on the truck. He mentioned it, said that's great, you'll get along well with our students. And so I did until retiring in May 2013. The first couple years I was posted at the old MATC Trade and Industry building across from Oscar Mayer on Commercial Avenue, just down the street from my terminal.

I'd worked myself into teaching computer programming to adult students, what I really liked, and there was plenty of maneuvering room in this big, complex bureaucracy. I figured all those years of organizational politicking in the labor movement served me well. In 2004 or so, I single-handedly challenged the Wisconsin Technical College System, our oversight body, when they were interfering with my classes - organized the students like you would in a union organizing campaign; everyone was shocked that not only could you do that, but win. I wasn't the most active member of AFT Local 243, the teachers' local at MATC, but paid my dues and supported the union in small ways and had fits of activism. One time out was to rally teachers and staff against the Gulf war in 1991 in concert with other labor people in the area.

Another foray involved a Local 243 officers election, where I supported one candidate for vice president over another. One of these candidates had been the president of Local 243 when it included just the teachers, before merging with the staff union around 2010. She took a break to work as a staffer at WEAC and took great exception to my WTCS campaign - she knew and had worked with those staffers, many of whom were union members. Just as I was breaking through to victory, she demanded I call it off. I said, what about the other teacher? She said, cut him loose. This is someone I had supported in the local, never mind her peculiarities, but when she came back and wanted to hold office again, I joined with others to stop her, sending mass eMails and personally talking to scores of people. She lost 55% - 45% and that might be one of the best things I did for Local 243 and the teachers. Later, she campaigned to get a good teacher fired when he complained about anti-Semitic treatment (which she joined in), using all the organizational wiles and connections acquired over the years - it looked like scab work, pure and simple. The teacher sued the dean and her sister-in-law, the HR chief, in federal court and was reinstated with a $1.1 million dollar settlement paid by the school. I'd been aware of the possibility of bad small group dynamics from stories about dysfunctional departments in graduate school and seeing it also as a driver, but this was not a small group - there were over 400 teachers. I ascribe it to the appalling lack of participation starting to infect Local 243. A single bad seed, however crazed, can have devastating effects even in a large group if they are the only one in the field without the counterweight of collective self-discipline.

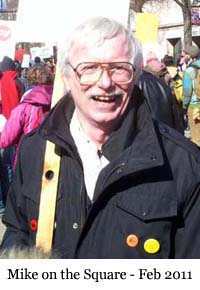

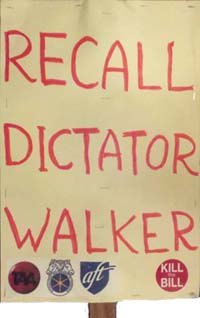

None other than Scott Walker pulled me in again in February 2011 when he passed Act 10, crushing our public unions in Wisconsin. The TAA was there in force the first day, rallying us all and bringing this little story full circle. I participated whole-heartedly with friends, students, family members, neighbors, and co-workers and must have put in a hundred circuits around the square during the rallies. I advocated and organized for the Walker recall and set up Recall Walker action groups in the neighborhood and at school before the recall was announced. It was like 1980 - you've still got a full-time job, but the organizing is taking up every other waking moment. I personally collected 512 signatures against Walker and our MATC group got over 4,300. The dynamics were familiar, with the official labor movement being supine and rank-and-file people taking matters into our own hands. Our political guy at AFT-Wisconsin said he thought the recall should be postponed till November 2012 (the official policy of the Democratic establishment in Washington). I told him to quit bothering us and stopped inviting him to meetings. The Union Labor News, official organ of the labor movement in southern Wisconsin, didn't publish a single article about the recall that I remember, except mine, arguing in September for the necessity to have a recall, and right away.

It was interesting who came around during the recall and who was effective. There was just about wall-to-wall support at MATC, but as always, people throw themselves into it to varying degrees. We insisted on meeting off-campus and had about ninety people at the meeting on the eve of the recall, arranging for Democratic recall staffers to train people. Even in this generally inactive group, people worked together effectively. It was different in some of the neighborhood groups, where many people wanted very much to participate, but literally didn't know how to. That's something about workplace organizing and the labor movement, people are in the habit of working together. Many of our best activists had a working class or union background or were gay. If it was all three, you just had to tell them where and when and hand them the recall forms. The concept of affinity groups resurfaced, an old one from the 60s and 70s. The idea is that small friendship groups can be the most effective in campaigns; of course everyone's on board with the mission, but what gets you out on the street day after day is not wanting to disappoint your friends, a variant of small group cohesion. I made many new friends, collected a lot of signatures, and had some fun.

Many public unions in Wisconsin had fallen into bad habits even before Walker toppled them over. There had always been a company union component at MATC, but a bona-fide trade union component as well, with good pay and benefits, an activist core, and union officials more-or-less willing to stick up for members in earlier days, if only to calm the waters (including that vice presidential candidate when on good behavior). But participation waned, activism attracting downright hostility (how very rude, they would say). This was distilled for me during the recall primary period. Our recall group had put scores of people into the field, over a hundred, an unheard of outpouring for this generally quiet group. Like so many others, I felt Kathleen Falk was a loser, with her ultra-left, last-ditch attempt to restore union rights - she promised if elected to virtually close the state down until bargaining rights were restored. The official labor movement was on board though, changing the name on the door from We are Wisconsin to Wisconsin for Falk literally over night, undeterred by polls showing she was going to badly lose the primary and also the general election if the candidate. We polled the action group, and it was almost unanimous that the AFT and the local should stay neural in the primary. I transmitted that to our local president, who sat on AFT-Wisconsin COPE and on the AFT-Wisconsin Executive Board. COPE voted neutrality, but the Executive Board overruled them and endorsed Falk, with the support of our president. I confronted him directly after that, explaining how you have to give members a chance to affect policy in a situation like this, where so many had a stake and had been participating. That that's how you attract people and build collective power, when it's their decision. He literally did not understand what I was talking about, saying, "But we've always done it like this." That is losing your way. Of course Falk lost the primary 58% - 34% to Tom Barrett, who himself lost to Walker one month later. The AFL-CIO didn't have the time or remaining resources (or interest, evidently) to campaign for Barrett. Rank-and-filers were reduced to printing our own Barrett yard signs and were handed literature not even naming Barrett when we went out to campaign.

I'm out now, but shortly after retirement participated in choosing a new president at MATC. The school sets up open forums for all candidates in a faux demonstration of openness. There is also a search committee including faculty and staff. We learned afterwards that the committee was a joke, members not given key information or allowed to ask questions. In fact, the school has strong authoritarian tendencies evident to any clear-eyed worker with time there, who knows that genuine input is the last thing the bosses want. I did some cold calling and found out that one of the candidates was a big spokesman for privatizing public community colleges, also that he'd apparently been fired from his last two jobs (the research department!). I drew up a leaflet spelling this out and distributed it with some associates to people coming into the forum - headline "Wrong for Madison, Wrong for MATC" and with his mug prominently displayed. The fellow himself walks in flanked by a couple vice presidents and I reached across one of them with a leaflet for him. Then in the question period I assailed him and in the middle of a back-and-forth asked, have you ever been fired before the last job? He said, what? I said, were you fired at Such-and-Such Community College in the late 90s? He admitted that he had, newspaper headlines ensuing the next day. At one point the dude says, you don't understand politics. Hey. He didn't get the job, Jack E Daniels did, an apparently much superior candidate from the point of view of the school and community, as well as the workers (we'll see).

Participation in Local 243 declined to its nadir in my last days at school, and right at the moment when it was most needed (the last labor agreement expires in March 2014). I still hold to those old principles learned at the feet of Bob Muhlenkamp and Jim Marketti and many others, themselves the heirs of Eugene Debs and the other giants of our movement: of course material advance is important, but so is autonomous worker self activity. The latter is not only a value in its own right, but is the surest guarantor of the former.

Mike Bertrand

November 9, 2013