J. D. Salinger

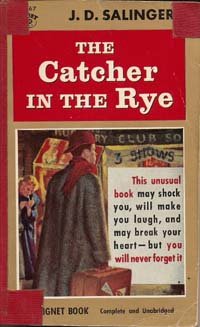

This unusual book may shock you, will make you laugh, and may break your heart – but you will never forget it

So says the front of my copy of The Catcher in the Rye (24th printing of the Signet paperback, December 1962), a wrenching picture of Holden in flight on the cover. J. D. Salinger, Rest in Peace, dead at 91 on January 27, 2010. Like my friend Dan says, a moment of note for boys of a certain age.

So says the front of my copy of The Catcher in the Rye (24th printing of the Signet paperback, December 1962), a wrenching picture of Holden in flight on the cover. J. D. Salinger, Rest in Peace, dead at 91 on January 27, 2010. Like my friend Dan says, a moment of note for boys of a certain age.

The Catcher in the Rye was my first hint that a book can hit the mark, a gentle introduction to the power of literature at the age of fifteen.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Beau Geste were good, high adventures, great entertainment. Holden Caulfield was on a different plane, a disaffected boy writing directly to us about every-day trials navigating the rough environment known as an American high school. Not bullets flying in the halls or rampant violence (it was a prep school after all), but enough coarseness to traumatize a sensitive boy. For Holden, it was not Ok to mistreat weaker boys in the locker room, it was not Ok to use obscene language in front of younger children like his sister Phoebe (after one such incident involving graffiti, he dreamed of being the guardian for children frisking in a vast field of rye, unaware of a cliff at the edge of the field -- he would be there to catch them before running off the cliff, the catcher in the rye). He encountered a classmate's mother on his travels, the son known only too well. "My son is so sensitive," she said (or close). "As sensitive as a toilet seat," Holden thought.

I wouldn't necessarily recommend assigning Catcher in high school either, as apparently has been done by a generation of male teachers remembering all this, trying to pass on the experience. Best to remember it as a period piece, keep it at the edge of the canon and let people rediscover it as happened the first time (the book was originally written in 1951 for adults). Girls tend to appreciate the book less, at least that was the case in my family. Think of the sweet classic Silas Marner, inflicted on untold generations of high school students with baleful effect, poisoned forever to the wonders of Victorian literature. It would be better if one in a hundred of those sufferers picked it up at age thirty-five on their own.

The book was spontaneously championed by kids, resisted at every step and for some time by the gatekeepers who called it obscene, all the more reason for rebellious youth to embrace it. My first letter to the editor defended Catcher in the Rye and tore into some philistine who wanted to ban it. Holden himself was the first rebel, skeptical of all things institutional and establishment, inhumane as they sometimes can be. For Holden, to be "phony" was the worst sin, the strongest epithet to be leveled. He respected children, no phonies there. Thinking back, it is remarkable that a cult classic for young adults (as we might say today), looks back to earlier childhood so admiringly.

I haven't read it since those days, but still remember (and still have my beaten-up paperback copy, see above). A catchy title, said I in class one day after Brother Paul said it was a stupid one. A rye remark, said he -- conventions meant little to Brother, a devotee of the anathematized Balzac (using the word literally here). He made some of the same observations being made here, not that I accepted them at the time.

So I took up Salinger's other books -- Franny and Zooey, Nine Stories, and all the rest, rarely to hit that peak again. Much of it was too adult for me and sad with so little hint of redemption or meaning (A Perfect Day for Bananafish, for example). One exception was his story For Esmé – with Love and Squalor, which hit home, adult as it was. A battle-scarred veteran told of things he'd seen in Germany towards the end of World War II, a cameo appearance only from the innocent and newly fatherless young Esmé back in England (maybe fifteen years old). It opens like this:

Just recently, by air mail, I received an invitation to a wedding that will take place in England on April 18th. It happens to be a wedding I'd give a lot to be able to get to, and when the invitation first arrived, I thought it might just be possible for me to make the trip abroad, by plane, expenses be hanged. However, I've since discussed the matter rather extensively with my wife, a breathtakingly levelheaded girl, and we've decided against it ...

A soldier's testament against war and macho culture, that's what I got out of it anyway, and that too was in the ether in the 1960s. I remember his witless girlfriend back home prattling on about psychology (she was taking a course), the exquisite scene with Esmé, and the Dostoevski quote from Alyosha Karamazov (from memory: "Brothers and teachers, I ponder, what is Hell? I submit that it is the inability to love"). This found in the effects of some Nazi underling.

J. D. Salinger made a mark and helped civilize legions of boys, that is a legacy to be proud of. Good bye, old friend.

-- January 30, 2010

PS: I just reread Esmé and got a few things wrong, not the basic take and certainly not my first impression of how fine this story is. Esmé was more like thirteen years old and scenes with her took up about half the story. It is Esmé's impending wedding, of course, and the narrator continues at the start:

I've gone ahead and jotted down a few revealing notes on the bride as I knew her almost six years ago. If the notes should cause the groom, whom I haven't met, an uneasy moment or two, so much the better. Nobody's aiming to please here. More, really, to edify, to instruct.