Unusual Books

Oddly enough, I wouldn't include most science fiction of my acquaintance in this category. Take that wonderful Philip K. Dick story where an itinerant handyman from around 1900 is transported together with horse and wagon to far in the future and interferes in major ways with the society of that time due to his preternatural mechanical ability and instinctive understanding of their advanced technology. It's a trick premise, but once granted, the changed physical and social environment depicted is well within reach. The people and their motivations, the political machinations, and so on -- all are similar to what you'd find in Jane Austen, given the different context.

A little further on the scale would be David Brin in The Uplift War, with his invading avian species and their weird leadership trinities. It was amusing to hear of the home "roost" and other such things, but in the end these birds and the sentient chimps were understandable and conventional. Something was done with the special mental powers of one benign trickster species and Brin is fun when in control of his plots and proliferating sentient species. It turns out that human beings are the only independently evolving, non-sponsored sentient species known in the five galaxies, "wolflings" that other species tend to react strongly to, good or bad (depending on their sense of humor). I was moved to read two others -- Sundiver and Heaven's Reach. They were less compelling, full of bizarre novelty for novelty's sake (although there are hidden gems, including a brief appearance by the hyper-aggressive, mantis-like Soro).

Ursula LeGuin is in a special category, how she weaves fantastic situations and communities into her tales and makes you think it is the most natural thing in the world -- the gender-changers in The Left Hand of Darkness or the thoroughly believable anarchist society of The Dispossessed. In the latter, a revolutionary movement some generations in the past breaks off and leads their people to a large moon of the main planet. Not unlike the Puritans of the 1630s who settled the American colonies perhaps, except the ideology is different and the new world is mostly barren. The old world is pictured as well, deep and refined in its own way, but showing only the iron fist to the hoi polloi. Anarchy does not mean a lack of organization; on the contrary, self-organization is at a high pitch and when people want to opt out of that, well, good on them. The entire population is deeply inculcated with the society's values (as with every society), so when general famine strikes, solidarity increases as the society mobilizes as one to meet the challenge.

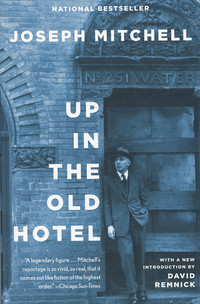

Now comes Joseph Mitchell's Up in the Old Hotel, one of the most unique books I've ever read (excerpt here). These essays were mostly published in The New Yorker between 1938 and 1964, where Mitchell was a staff writer, and bundled into this book in the early 1990s, 700+ pages of them. The subjects are generally odd and interesting people and sub-communities of New York City and the first temptation is to think, "This has got to be fiction", but I don't think it is. For one thing, whenever Mitchell states facts (and he does a lot of that), they are accurate to a fault. His narrative style is matter-of-fact and has the cumulative effect of generating sympathy for his subjects, even while the uncomfortable feeling gnaws at the back of your head that the good feelings might be somewhat reduced were you there in person. Even his New York rats merit a moment of empathy as he relates their overriding dread of human beings (as well as the inadvisability of cornering one, plague stories, and so on).

Now comes Joseph Mitchell's Up in the Old Hotel, one of the most unique books I've ever read (excerpt here). These essays were mostly published in The New Yorker between 1938 and 1964, where Mitchell was a staff writer, and bundled into this book in the early 1990s, 700+ pages of them. The subjects are generally odd and interesting people and sub-communities of New York City and the first temptation is to think, "This has got to be fiction", but I don't think it is. For one thing, whenever Mitchell states facts (and he does a lot of that), they are accurate to a fault. His narrative style is matter-of-fact and has the cumulative effect of generating sympathy for his subjects, even while the uncomfortable feeling gnaws at the back of your head that the good feelings might be somewhat reduced were you there in person. Even his New York rats merit a moment of empathy as he relates their overriding dread of human beings (as well as the inadvisability of cornering one, plague stories, and so on).

He writes of McSorley's long-standing saloon in the first essay, with due attention to the sour proprietor and his extreme aversion to change, professionally speaking. He grudgingly had the ceiling repainted after patrons (not particularly change-mongers themselves) complained of paint flakes falling in their beer. Prohibition was a minor inconvenience for McSorley and gang. Apparently the author did a bit of field work in the place over the years. A North Carolina boy headed for the big city, a Thomas Wolfe of non-fiction, Mitchell seemed to get a kick out of all things New York and all things old and off-center. Put the three together and he had something to work with. He has more than one character in their nineties and revels in such things as an old-time African American cemetery in Staten Island:

When things get too much for me, I put a wild-flower book and a couple of sandwiches in my pocket and go down to the South Shore of Staten Island and wander around awhile in one of the cemeteries down there. ... Invariably, for some reason I don't know and don't want to know, after I have spent an hour or so in one of these cemeteries, looking at gravestone designs and reading inscriptions and identifying wild flowers and scaring rabbits out of the weeds and reflecting on the end that awaits me and awaits us all, my spirits lift, I become quite cheerful, and then I go for a long walk (from Mr. Hunter's Grave).

Some of his characters are certifiable, like old Joe Gould, some just different, like trawler captain Ellery Thompson out of Stonington, CT. Ellery (what Mitchell calls him due to the captain's suspicion of anyone who calls him anything else) took up painting when his mother's interest in the subject couldn't be renewed on one occasion (what the heck, he had all those unused art supplies on hand). He liked it and was good at it, having no problem selling paintings to afficionados as a "primitive" and to fellow captains when they want a picture of their boat. The other captains became tedious when demanding to see their boats in ever more extreme storm conditions, one feeling a bolt of lightning touching the mast would have improved the composition. Suspicious at first, Ellery ended up helping and befriending a couple of oceanographers from Yale, whom he hosted regularly on fishing trips, going so far as to use the Latin name for a fish on one occasion, though profanely denying it later.

Mitchell has a highly developed sense of ecology and he writes of rural or small-town areas actually within the city (Staten Island) or close, as with the New Jersey Palisades right opposite Manhattan, literally within sight of city sky-scrapers (the small-town ambiance a thing of the past, I'm guessing). His rare editorial comments, elliptical even then, usually concern some ecological atrocity, like the waste inherent in Ellery's kind of trawling, where some half of the organisms netted up are thrown back, often to die, despite their being edible and even a delicacy if properly prepared. More often the facts speak for themselves, like how the rich clam beds of New York Harbor had to be ruled off-limits in 1916 due to their poisoning by massive dumping of raw sewage.

Gypsies, cops, odd museum proprietors, high-rise Mohawks, fishermen, river-lovers, campaigners against swearing, denizens of the fish market -- these are some of his subjects and often they are quoted extensively, allowed to tell their own story. Joseph Mitchell has a special narrative voice not quite like anything else, not just unusual, but unusually good.

Mike Bertrand

January 24, 2010