Pittsburgh

Flying back to Pittsburgh with an old Elmore Leonard in hand (The Big Bounce, 1969) jogged some memories. Our man Jack Ryan, someone pulled his chain, the same phrase an upperclassman used on me the first day on campus in August 1969 and the first time I'd heard it. You're in the big leagues now, boy.

Flying back to Pittsburgh with an old Elmore Leonard in hand (The Big Bounce, 1969) jogged some memories. Our man Jack Ryan, someone pulled his chain, the same phrase an upperclassman used on me the first day on campus in August 1969 and the first time I'd heard it. You're in the big leagues now, boy.

What a great English teacher the first semester and after a string of them in high school; the reading list as much as anything - he was a part-timer and probably wanted an excuse to read or reread some favorites. He had Swann's Way under his arm one day. For us it was Iris Murdoch (The Severed Head), Hard Times (Gradgrind!), and Middlemarch, the last my all-time favorite after many re-readings. I remarked in class one day that among the main characters in The Severed Head, almost every possible romantic combination had been consummated or at least entertained. He liked that and rejoined that two female characters were always touching each other, seemingly casually or mistakenly, he thought it was pretty funny. He was making the point with us one day that people can walk through their own lives as zombies without even noticing their remarkable surroundings, most appropriate in the immediate environment of Pitt with the amazing buildings. He said, consider the Civil War Museum, how many columns are there in front of it? Eight, I said (Math Department reporting). He was a little miffed, as if I'd interfered with his lesson.

We wrote about what we read, like in high school. Still doing that. He took off on the Catholics once, how they still have a list of prohibited books, the Index. I objected, saying no one paid attention to that any more. He disagreed and I didn't have the gumption to say that Balzac's entire oeuvre was on the Index and that didn't stop Brother Paul one bit from loving and assigning him to his third year high school students at South Catholic. Another lifelong compulsion avocation, Balzac. Brother assigned Eugénie Grandet, probably the best choice, having recently reread it. The curé was stone cold cynical and such characters are probably why he ended up on the index, conservative monarchist that he was, but a minor character. Think of Eugénie or her father, one of the great misers in world literature - I think Balzac even said at one point there is a certain grandeur in one so devoted to his all-consuming vice. I'll never forget Brother laughing about how old Grandet reached greedily for the golden cross held out by the priest at his moment of death.

Yes, high school was parochial, but it was good and eclectic in its own way - Brother marched us through Luther's A Mighty Fortress is our God for months for graduation day, even though he had a tin ear he once confessed (in Physics class). So what to take first semester. Math and English of course, Russian for language rather than Latin (вы говорить на русском?; first sentence in the textbook: Я иду на почту - never could roll my Rs). But what about religion class? Never mind that the old faith is going or gone at that point, it's part of the curriculum. Well that would be philosophy. It was an intro class and one of our papers was on the mind-body problem. I had something to say about that and asked Mom to type it up, but the TA said it had to be on one page or he wouldn't even read it, so it was type from margin to margin, top to bottom and side to side. Mom laughed, the grade was good. I took probably ten Philosophy classes at Pitt (Philosophy and Physics minors), including a couple that were outright math classes on logic in this analytic department - those poor Philosophy graduate students, they didn't have the first idea.

They'll let you into the nationality rooms at the Cathedral of Learning by paying a small fee - maybe next time, although newer ones on the third floor are open for inspection (the Turkish room is amazing). I had a class in the German room on German literature in translation. The professor was a tall, thin, blond Nordic type and left an abiding impression of the heights of German humanism and (implicitly) the depths of human self-degradation to forswear such a legacy. Heinrich Böll is a continuing pleasure - he assigned Billiards at Half past Nine, but The Clown and Collected Stories are also remarkable. One day class discussion on Buddenbrooks focused on how timid the family had become, how that was the root of their downfall; and class members were piling on. After a bit, I said it was just the opposite the other day, how they were too adventurous, downright reckless, that was what did them in - it seems like they're damned if they do and damned if they don't. Rather than object as I expected, Professor smiled beatifically and said, yes, did you notice the subtitle - The Decline of a Family. That was the high point of my career as a literary critic. In an informal moment later, a TA asked if I'd cribbed that from some critic she cited.

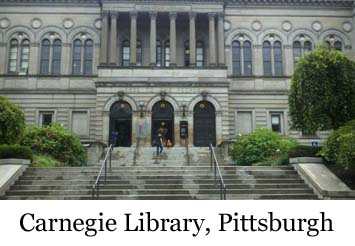

The Cathedral of Learning is remarkable, that big vault on the first floor - how can it not inspire higher thoughts sitting there in repose. Then there's the Carnegie Library right across the street, a wonderful gift from that old reprobate, one of thousands across the country. Gospel of Wealth my ass - I'll break you for a generation, then give it back. My sister showed me where he is buried, a rather impressive Presbyterian church in East Liberty. At least he had some style as a philanthropist. I used to go over as an undergraduate and sit in a cushy chair (such furnishings in reading rooms were much less common then). I remember studying Calc III in one of those chairs. Also falling asleep once and a guard asking me to leave. Part of the Portia speech is engraved out front under a statue (The quality of mercy is not strain'd, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven upon the place beneath ...). The Merchant of Venice was standard for first year high school then, no doubt replaced since because of its uncomfortable anti-Semitic aspects (although Shylock's speech too was stunning and will be till the end of time - Hath not a Jew eyes?).

I hit the Original Hot Dog Shop - just like the old days, except now you can sit down - with chili, onions, and mustard please, and just small fries (ha). Well, the old gnome wasn't there - he'd be 125 by now. Like the soup Nazi, except without the smile. Small of stature and doubly so bent over like he always was, probably from fifty years of hard labor. Say what you want and don't waste my time. I saw my first semester Philosophy professor in there once, dressed to the nines and a bit affected, but standing up to the bar like the rest of us plebeians. He was good though. I took a second class from him in aesthetics and once hazarded the opinion that mathematics was an art - a bit provocative, granted, but he didn't have a very good answer (schools always place it together with science).

Working class Pittsburghers have some unusual usages; most notably pronouncing ow sounds as ah, at least if there's a consonant following. So down town is pronounced dahn tahn (each word rhyming with don or con). Washington, a town a bit to the south, is Little Worshingon (George Washington saved the day one time in the vicinity when that dolt Braddock was killed and almost took everyone with him). Infinitives are deprecated: "this needs to be done" becomes "this needs done". Apart from being gods, the Steelers are the Stillers. The first one seems to have continued full force. I'm guessing a Polish or eastern European origin. It was notorious how many languages were spoken in those mills as late as 1920; everyone had to learn English just so they could talk to each other. Another charming practice is that people of opposite sexes routinely call each other honey or dear or similar. I've had fifteen year old clerks young enough to be a granddaughter call me dear.

When I lived there, Pittsburghers were quick to toot their horn if you didn't leap out from a light, that was annoying. I didn't see it this visit, and in every other respect these are the most courteous drivers in the country. They almost always let you merge. If you're stopped at a light and need to take a left turn across oncoming traffic, standard practice is for the oncoming vehicle to wait for you to take the turn before proceeding; try that anywhere else.

My summer jobs in college: the first year was in the blooming mill at the Jones and Laughlin South Side Works along the Monongahela. All gone now and gentrified; steel has left Pittsburgh long since. Finish high school Friday, stop by the J&L hiring office on Saturday, start on Monday. The name on my birth certificate was Al, so that's what they called me all summer, an alias for this new life. Senior steelworkers had thirteen weeks off every five years or so, they needed college kids to fill in. That was a trip, forces you don't see in everyday life - heat, weight, and noise. We wore heavy clothing to ward off the heat, just as a physical barrier. Every day or so they would bring in a giant ingot, twelve feet or so tall, just let it sit there for a few days to cool. It was the shape of an old fashioned milk jug, gray on the outside, still molten on the inside at first. The purpose of the blooming mill was to squeeze that sucker down into rails, whatever the spec was for a given job. They'd send it down through big rollers, squeezing it smaller and longer a bit every pass. It turned orange pretty quickly and started releasing heat, serious heat, you couldn't get too close.

The sound was beyond anything I've ever heard. You couldn't hear someone hollering right next to you. We had signals, like breaking a twig to say time for a break. No ear protection, of course - what are we, a bunch of weenie asses? My job title after a few days on the work gang was scarfer helper - it involved cleaning under the horizontal rollers moving the steel along. There was a little waterway under there to carry away the steel particles that sloughed off. There were little footholds above the water and you had to bend over and use a pry bar to clear the jams. This when the mill was down, of course. Except the one time I got caught down there when they started up the mill. That was memorable - you never saw a kid move so fast in a cramped space. My thick shirt was pock-marked from burning cinders.

Coke cars would come in by the hundreds; one of my jobs was to help empty them. They would be brought along the track over a pit, then the covers underneath opened for the coke to fall below. Except sometime it was jammed, so you had to apply gentle persuasion via sledgehammer on the side of the car. On occasion we'd be asked to "double out", meaning work two shifts back-to-back. You'd be staggering around towards the end of that. After a double out graveyard shift (3:00 pm to 7:00 am on the job), we'd repair to a seedy bar, one on every corner in the South Side in those days it seemed. "Shot and a aaarn (iron)", it hardly even had to be said. Iron being Iron City Beer, a staple to this day - a shortie (seven-ounce bottle) was fine to wash down a shot. I was familiar with the concept, because that was Dad's approach. Maybe two of those and then wobble over to the bus stop. I asked a waiter on this trip if they had Iron City Beer; he smiled and said he'd check, in a tone indicating he thought they had water too.

The second summer was at a St Regis box factory. Most of our orders were for Heinz across the river - they sent the finished boxes over by barge (broken down). Some jobs required a little razor ring for your pinky, a little crescent stood out with a razor on the inside; that way you can quickly cut the twine used to collect together the collapsed boxes. I'd worked there a few weeks when one Friday the supervisor stopped by and said, Al, you're on corrugater pickup next week. It meant nothing to me, so I asked the other guys what that was. Geez Al, you've just been here a few weeks and they want you on corrugater pickup already, that's hard. They downright terrorized me. Only to find on Monday that the talk was mild compared to the fact. Again with the rollers, this time starting from three huge rolls of thick brown paper that fed into a long stream of hot glued new corrugated cardboard, the middle roll the corrugated layer. It was cut in both dimensions coming down the line, as required by the order, then a couple of us at the end of the line had to pick up ten pieces or so in unison, align them, and stack on palettes. Hot, dirty (cardboard dust!), heavy, and most taxing, hard on the hands. It turns out that cardboard can be incredibly sharp at the edges and yet gloves are out of the question, considering the dexterity required. The button pushers upstream were on incentive, so always wanted to speed up the line, then settle in on lawn chairs to catch up on their skin magazines. A half hour, an hour, it was impossible as filled palettes were carted off and empty ones brought up. The guy across from me winked, then stepped back and let the cardboard start piling up. I did the same and the entire line came to a crashing halt. The button pushers came running down hysterically, one of them actually waddling he was so out of practice. Gotta get this cleaned up right away so we can start up again. We stood there laughing as they cleaned it up.

We wore tee shirts in the plant and sweated like pigs. The guys would pinch each other's nipples, I mean give it a real good twist - male bonding at its finest. I formed a friendship with Elijah, a quiet and friendly fellow with a terrific physique. He was intrigued by me being a college student - someone from a different world. And he intrigued me too. He was a veteran, and not too long out after stints in Vietnam. He told me he had gotten into trouble in the South, he was just passing through in his dress uniform. A white guy at a bus station didn't think he was in quite the right section or something and stepped on his shiny dress shoes, staring at him nose-to-nose. Elijah put him in the hospital, figured he just had too.

The third year was at a rendering plant on an island in the Allegheny River. Drivers would collect inedible meat from butcher shops all over the city and we would turn it into tallow and a dry residue destined for pet food or whatever. It all went out by rail - the tallow in tank cars, the solids in box cars. That's where I learned to roll a heavy fifty-five gallon drum along on its rim and even toss it over into a pit so that it caught on a bar, the contents tumbling in, the drum to be pulled back up empty. One of the guys worked a little front-end-loader to push scraps down into the pit. He'd stop cold sometimes, climb out above the blade and snag something promising with a little hook, then wink at me and say, lunch. "That's all she wrote" was his favorite expression. The boss was an older gent who worked right along with us - a real sweet guy except when it came to bad behavior (like racial innuendo); even then he was mild, but got his point across. He noticed me out on the street one day on my Honda 150; he was with his family and brightened up right away and said, "There's Al!".

The last year was with a labor pool organization, all kinds of jobs. I met some nice, hard-working people, many homeless, and spent some time with them in bars after work, then took a bus home as they went back to their day-rentals, all ready for work the next day. These jobs paid my tuition and books at Pitt for four years, something that is out of the question all these years later with the depressed wages, ridiculous tuition, and $50,000 of student debt for undergraduate school. United Steelworkers of America, thank you.

I finished The Big Bounce on the plane back. My seat mate glanced over and said, Elmore Leonard, didn't he just die? Tuesday, I said, he's the best, the very best, have you read him? No, but always meaning to. When done, I gave him the book and he started reading it. Then I reached for my Balzac (The Fatal Skin, a 1963 Signet paperback).

Mike Bertrand

September 18, 2013