The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

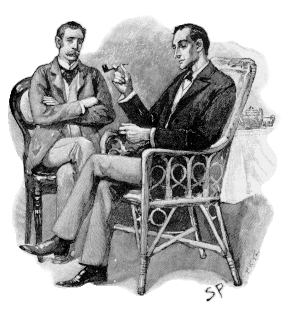

The great mathematician Niels Abel encouraged all to study the masters rather than their pupils, good advice in the case of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Inspired by the Jeremy Brett adaptations from British TV, excellent in their own right and meticulously faithful it seems, I took up the hardcover Castle edition, complete with the original Sidney Paget illustrations ($8.00!). Conan Doyle released the first twenty-four stories between July 1891 and November 1893, and finished Holmes off in the last one (The Adventure of the Final Problem). The hero returned in The Hound of the Baskervilles and thirteen more stories (The Return of Sherlock Holmes) from 1901 through 1905. All were serialized in The Strand magazine and are about fifteen pages long in my edition, excepting the novella length Hound.

The great mathematician Niels Abel encouraged all to study the masters rather than their pupils, good advice in the case of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Inspired by the Jeremy Brett adaptations from British TV, excellent in their own right and meticulously faithful it seems, I took up the hardcover Castle edition, complete with the original Sidney Paget illustrations ($8.00!). Conan Doyle released the first twenty-four stories between July 1891 and November 1893, and finished Holmes off in the last one (The Adventure of the Final Problem). The hero returned in The Hound of the Baskervilles and thirteen more stories (The Return of Sherlock Holmes) from 1901 through 1905. All were serialized in The Strand magazine and are about fifteen pages long in my edition, excepting the novella length Hound.

First it is necessary to rehabilitate the estimable Dr. Watson, an intelligent and sympathetic narrator who has suffered at the hands of less faithful and dextrous earlier interpreters. Just the fact that he recorded these adventures and understood their value to posterity speaks in his favor, not to mention his standing as a master story teller and fine Victorian gentleman. Holmes's confidant and number one man as well ("Meet me in the square at 11:00, my dear Watson, and don't forget to bring your revolver"). It wasn't always easy living with the single-minded detective either. Watson married during the course of these adventures and established his own medical practice and household away from Holmes's Baker Street rooms, not that it impaired the collaboration.

Holmes aspires to master every facet of the detecting art, including biota, chemistry, human behavior, and social mores. His observational and deductive skills are legendary, also a power of concentration verging on self-hypnosis. Even his friend is well-advised not to interfere at such times, while outsiders (including clients and the police) are left in a state of misunderstanding if not annoyance. He is a master of false disguise and impersonation. Robust and physically strong, it would not occur to him to exercise in any way except in furtherance of cracking a case (and there is plenty of that). False modesty is foreign to our archetypal detective. It is not so much that he is willing to stoop to all fours or go flat on his stomach to investigate some detail in a patch of muck. Rather you could not stop him from doing so anymore than a spider could be stopped from weaving her web. It is his essence and his joy to solve mysteries.

Holmes's method is to interview, visit critical scenes and persons, then deduce based on his observations. Far from an armchair intellectual, Holmes revels in the chase and is often to be found apprehending malefactors, the prospect of personal danger meaning about as much as a dirty patch on his trousers. The police have learned to respect him by experience or reputation, but are guarded or even resentful (especially the dull ones). Aware and generally respectful of legal restraints, Holmes has no scruple about testing the limits of the law once he is sure of his man and the way to catch him.

Watson is valuable as a foil and helper within the stories, but also as a literary device, conversations between the two being the mechanism for the accounts to unfold (Holmes sometimes laments these explanations, since they seem to detract from what are otherwise regarded as near magical insights). One story opens with Holmes examining a hat left at the scene of a crime as Watson comes to visit. Watson sees nothing to identify the owner, to which Holmes says:

Watson is valuable as a foil and helper within the stories, but also as a literary device, conversations between the two being the mechanism for the accounts to unfold (Holmes sometimes laments these explanations, since they seem to detract from what are otherwise regarded as near magical insights). One story opens with Holmes examining a hat left at the scene of a crime as Watson comes to visit. Watson sees nothing to identify the owner, to which Holmes says:

It is perhaps less suggestive than it might have been and yet there are a few inferences that are very distinct, and a few others which represent at least a strong balance of probability. That the man was highly intellectual is of course obvious upon the face of it, and also that he was fairly well-to-do within the last three years, although he is now fallen on evil days. He had foresight, but has less now than formerly, pointing to a moral retrogression, which when taken with the decline of his fortunes, seems to indicate some evil influence, probably drink, at work upon him. This may account also for the obvious fact that his wife has ceased to love him.

"My dear Holmes!", exclaims Watson, speaking no doubt for many readers (explanations follow in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle).

Like other good writing of its time and place, there is much to be learned about the social milieu that is pictured -- that which has changed and that which has not. Holmes's clients tend to come from the upper middle classes and above and they illustrate their class and time just as that old world of kings and landed gentry was about to fracture. Holmes is the last man to be affected by superior social standing, showing fair contempt for one regal client who failed to show proper respect for a commoner Holmes regarded as more than his equal (a lady who bested Holmes himself and one of few who ever did -- see A Scandal in Bohemia, Conan Doyle's first Sherlock Holmes mystery).

I'm going to speculate that Sherlock Holmes has had a pronounced effect on the detective and mystery fiction that has followed. There is so much in common, including the principal's intense absorption in work. As The Adventure of the Reigate Squire opens, Holmes is seen recovering from nervous exhaustion, having worked fifteen hour days for weeks on end to solve a case. Nudged by Watson to a country retreat to recover, he is confronted almost immediately by a murder at a neighbor's estate, just what the doctor ordered! Then there is the observation and deduction, the working out of clues, and the attention to power dynamics and awareness of social background found in much of such fiction. Writers and readers alike, we may owe a great deal to Conan Doyle even beyond his great creation, the supremely competent and confident, always interesting and admirable Sherlock Holmes.

-- June 21, 2009