High School English

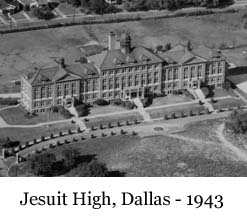

I always laugh when people deprecate Catholicism as mindless superstition, because I know better from direct experience as a product of four years of Catholic high school. I started out at Jesuit High in Dallas in 1961. Mr. Joubert was my home room, religion, and English teacher. A lot of French names - it was the New Orleans Province after all, not missionaries from Chicago (like my grade school, St. Luke's in Irving). So a tip of the hat to Mr. Vavasseur, my sophomore geometry teacher, a tall, skinny, kind and intelligent man who knew and valued his subject and also knew how to transmit intellectual excitement. He was an important milestone in my mathematical education, especially considering that geometry is where students first encounter the axiomatic method and proofs, the cornerstones of modern mathematics. Between proofs, Mr Vavasseur regaled us with stories of how geometry had been the canonical science for two thousand years, even people like Spinoza modeling their philosophical speculations on Euclid. He quite rightly mentioned Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri, S. J., who foreshadowed non-Euclidean geometry. He was hell on wheels when crossed though; I remember him thundering more than once, "I'll be in Room 214 after school, Jones, be there" (emphasis on the last two words).

The Jesuits had a system where after some graduate education, but before advanced theology, the "scholastics" (as they were called) would spend three years teaching in a Jesuit high school. They were usually 26-29 years old and it was a great system populating your staff with these smart, enthusiastic young Jesuits starting their careers, many never to return to high school teaching. Mr. Bayhi taught us Latin - four years of that, starting with bowdlerized Caesar (Veni, vidi, vici), but then the real thing for Cicero and Vergil later on. Kids complained - how archaic can you get. Our teachers would say hey, you might become a pharmacist or botanist. After the laughter subsided, they'd talk about Latin as the root of the Romance languages and contributor of so many words to English, how studying grammar in a highly structured, declined language like Latin can help you understand your own language. The fact is, they were steeped in a classical sensibility, Rome being the civilization that gestated Christianity, and wanted to impart that to us. And not just Christianity really, but Europe generally, built as it was on that old foundation. Variations on these points were made by none other than Antonio Gramsci in the Prison Notebooks. Gauss himself wrote in Latin as late as the 19th century, including the path-breaking Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, duly translated into English by Arthur A. Clarke, S. J.

There was a lot of writing in Mr Joubert's class, typically about what we had read; I suppose he considered teaching writing one of his main tasks. He was exacting too. Once when we had all disappointed him in a writing assignment, he gave it to the entire class. He did not approve of going through the motions. If you're intellectually limited, that's fine, but not giving it your all every time, well that's not acceptable. Looking back, these were people who understand the young and know how to mold minds. Well yeah, it's the Society of Jesus and they have specialized in education from the beginning; the Reformation was a blip for them. They would talk about the Christocentric approach to history in religion class, then drop it cold in history class. Sometimes a kid would bring something like that over and the teacher would give a grim little smile indicating "Lord, another simple one", but would say out loud, "This is history class, Johnny". They believed what they said in religion class, believed it deeply, but also believed (and would tell us) that God gave you reason to use it; that too is doing the Lord's work. After punctuating that last sentence, I remember Mr Joubert once confiding to us that overuse of parentheses was his particular weakness(!). So it was planted in me at an early age and not really my fault at all. There was a bit of public speaking. Mr Joubert told of an earlier student who had given a speech with fly open and they told him. Next speech the kid takes his place at the front of the room and before starting looks down at his fly conspicuously to general uproar. "Not the way to do it", said our laughing teacher. 29 years in the classroom and not a single fly down (that I know of), thank you Mr Joubert.

When we were reading The Merchant of Venice, he asked if anyone knew what a strumpet was (the strumpet wind in Act 2, Scene 6). Unfortunately I did, and said so in a childishly inexpert way. He led the class in laughing (he put his head on the table and just about sobbed). Once in religion class he posed the dilemma of a Jesuit who had led an exemplary life in every respect, but succumbed to a woman one night and died immediately after. How is that fair, going to Hell for one weak moment. He acknowledged that this was a tough one and even gave the impression he would consider mercy, but did say that sometimes people plant the seeds of their downfall and make their ultimate decisions long before the fatal act. That's a lot to think about for a fourteen year old kid.

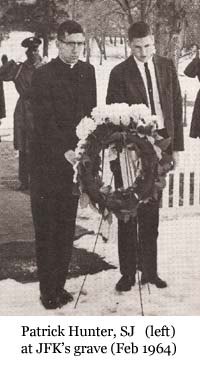

Patrick Hunter, SJ, was my religion, English, and home room teacher sophomore year (Room 209H - the H for honor, but just the second honor class evidently). His mother was a Perilloux. Mr Hunter was one of the most remarkable people I've ever met and made a deep impression. He treated us like adults even though we were dumb kids. We had a short story reader, probably chosen by someone else, and the first week he assigned two stories from the middle of of it - Chekhov's Gooseberries and Bliss, by Katherine Mansfield. Gooseberries is a little story within a story - seemingly artless, but memorable in a special way known to Chekhov readers. It concerned a poor government clerk, now retired in the country after a life of slaving and saving for his little patch in the country. This is all from memory - the narrator witnessed him greedily devouring his cherished gooseberries, slobbering and making a spectacle of himself. The narrator, healthy and in the prime of life, felt nothing but compassion for this thwarted character. He said something like, "We must remember at all times that there are people in pain; we should have someone in the wall knocking on occasion to remind us." Bliss was about a character at a dinner party, here too from memory. She was feeling euphoric, especially about her husband, and this went on for some time before she noticed unmistakable signs that he was having an affair with one of the guests. I didn't even know what an affair was, but got the basic idea, as with Chekhov - complacency is not in order, ever; self-examination is. There were layers of lessons and I vaguely understood what was happening even at the time, including that art is transcendent.

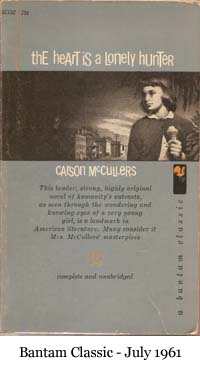

I think it was Mr Hunter who assigned Carson McCullers' The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, presumably as an acceptable introduction to southern gothic literature for young apprentices like us. It didn't do much for me and time to try it again, see what I missed. Our English teachers would talk up Flannery O'Connor, southern and Catholic. I've read a bit of her since and can only thank God she was never assigned, ruthless cynic and bible thumper at the same time. She explained in essays how the activist upsurge of the day and even civil rights legislation were worthless, because they don't change the human heart. She died in 1964 and perhaps would've changed her tune had she lived to see the changes wrought by civil rights legislation passed just as she was dying, including changes to the human heart, and quickly. But I doubt it; the phrase "invincibly ignorant" comes to mind, one I learned at Jesuit High School.

Without question, Mr Hunter got me started in a life of crime as an activist. The school had a food drive and we Irving kids put our shoulders into it, wouldn't want to disappoint Mr Hunter (it was organized by home room). He approved. Mr Hunter was involved in the civil rights movement in Dallas, peaking like everywhere else in the 1962-63 school year. Once that year I had a date with a cute little girl and went in to meet her parents before the dance. They railed about race mixing and such, supposedly cultured people that they were. I think I gave them a little backtalk, not even sure any more, but it made an indelible impression and I wrote a story about it. A sophomoric attempt, no doubt, but Mr Hunter approved of that too - getting in practice for the life to follow. He was studying up on adolescence - for professional reasons I suppose - but was enthusiastic in sharing his findings. Adolescent rebellion, and so on; I smugly thought I was beyond that stage (ha).

Speaking of which, we had a right-wing lay history teacher that year, a dim young guy, but earnest and very much reflecting the hard conservative ambiance polluting Dallas in those days. Just to pimp him, I wrote a long essay on how Jesus was a socialist, not a godless communist mind you, that's totally different. Really made the case as well as I could - the attention to the poor, the collective mentality he tried to engender, the revolutionary political aspect, and so on. We used pens with cartridges of purple ink - something I would never recommend in a boys' high school incidentally, talk about asking for trouble. But there it was in purple, page after page in my juvenile script, AMDG (Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, the Jesuit motto which we always put at the top of our papers). The teacher didn't like that one bit, there was more red than purple when he gave it back, prominent being "See Smith's paper for the truth about this", Smith being a right-wing student in synch with his Lordship. I showed it to my buddies and we laughed our butts off. He did assign de Tocqueville, give him that.

The thing about Mr Hunter, he was never one to pass up an opportunity for enlightenment. In a private moment once, I complained to him about my Algebra teacher the year before - how rigid he was, almost dead, and this in a subject I was really interested in (and eventually made into a career). He was an older man, a priest. Teacher looked at me a little sadly for a moment. I've often wondered if it was disappointment, as in "Mike, I'd thought you've been coming along faster than that", but he probably needed a second to think how to handle it, how to choose his words. He said, "You know, he may be giving it everything he's got, just barely holding on". That's all he said. I knew it was exceptional even at the time, talking like that to a dumb kid like me about a member of his most sacred community, someone who was probably his superior. He didn't deny it, he explained it. That is a lesson in charity, thinking the best of someone that you possibly can, and worth a year of religion class. And charity to me too.

Mr Hunter was into poetry and assigned Laurence Perrine's Sound and Sense. That's an awfully good book and I'm guessing typically found in college classrooms. We'd beat out iambic pentameter and focus on how very compactly you can say something when you try. But mostly, just breathe in our wonderful language. At one point, he organized his fellow Jesuits into a little poetry contest (my Algebra teacher must have wanted to wring his neck). The only line I remember was from another young scholastic who died soon after from an incurable disease, "Life is a deep deep sea, dive in!". Mr Hunter introduced us to the Greek alphabet in religion class one day - he slowly went through the entire alphabet, showing lower and upper case letters and making comments that may or may not have had a religious bearing (ΑΩ, π). His favorite letter was ξ (fun to write with all those squiggles). Of course that's good grounding for the budding mathematician and I've always brought in ξ myself whenever the opportunity arose.

Mr Barfield was my English teacher junior year. He was older than most scholastics by twenty years or so and seemed to have some miles on him, dour but smart. His most lasting effect was preaching the value of seizing every spare moment for reading; he'd say you'll be surprised how much you can read in spare moments throughout the day, but you have to be mindful about it and have a book with you at all times. I read many a volume that way as a truck driver. Not the only one either; in the day, maybe 20% of my peers were readers. They wouldn't admit it though and would drop the book right away if you came up to their driver side window when there'd be a bunch of us lined up at some big warehouse. I remember reading Balzac's Lost Illusions that way and at a time in life where it spoke to me - smart but penurious young Lucien de Rubempré comes to Paris from the provinces, turns the tables on talentless but ruthless enemies from the old home town (the Stork!), falls in love with the beautiful actress / courtesan Coralie, and becomes a successful journalist / con man (about the same thing in Paris circa 1835). There is the scene where Coralie, about to go on stage, spies him for the first time through the curtains and falls irrevocably in love.

My math teacher in junior year was a lay teacher who dressed impeccably, drove a Harley into work, and was reputed to be an atheist. Now that's interesting, no matter how devoted a person might be (I would still serve mass on occasion at this time - just walk into the sacristy and put on cassock and surplus at St Luke's when they were caught short-handed). The first day we were all dying with anticipation. He stands at the front of the class and bows his head as a signal for the short prayer we always said at the start of each class. We noticed he wasn't actually joining in the prayer - aha! He sits down, picks up a book, tosses it aside, and says something like, "This book is garbage, I'm going to teach you kids something you can actually use". He proceeded to give us a nice little course in propositional logic - truth tables, disjunctive normal form, the works. Of course it is something I've used ever since, especially when flirting with being a mathematical logician, but in many contexts throughout life.

Our vice principal was a rather stern gent - not unkind, but come on, he's the school disciplinarian. One day he used the word "promulgate" over the broadcast speaker and hilarity ensued in many classrooms. He was livid, over the top it seemed for a generally mild fellow. I get it now though. He wasn't going to be bullied out of his mission of civilizing Catholic youth by any amount of boorishness. He upbraided us in no uncertain terms. I've used "promulgate" at every opportunity ever since. I would put AMDG at the top of all my papers for years after leaving Jesuit, it became a habit and the first thing you'd do without thinking before starting to work.

In junior year my family moved to Pittsburgh PA and I started at South Hills Catholic High School (South Catholic), run by the De La Salle Christian Brothers, another teaching order. I hardly gave them a chance at first, Mr Hunter's lessons in tolerance apparently not taking. My mistake and pretty obvious when Brother Paul arrived on stage. He loved literature, everything about it, and enjoyed the New Yorker. Balzac was a favorite, officially anathematized though he was. He assigned us Eugénie Grandet, which after rereading I'd put in the top twenty novels I've read, lifetime - so tight and full of life, in spite of Balzac's chaotic methods and prodigious output (no word processors or even reasonable pens in his day). Brother laughed heartily at the scene where the miser old Grandet reached for the golden cross held out by the priest in his moment of death. Also Graham Greene's The Heart of the Matter, which (amazingly) concerns the perils of taking Catholicism too seriously - the protagonist Scobie was a convert, as was Greene. I'll never forget the scene in church where he figures he has to take communion to convince his wife he's not having an affair, though he is and she knew it. To be clear, that is a pretty big sin, taking communion while in a state of mortal sin. Greene actually tracks Scobie's torment as the mass proceeds - Kyrie eleison - Christe eleison - Kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy). At the time I could hardy believe Brother assigned the book, as grown up and sophisticated as it was, but certainly appreciated it.

Brother assigned The Catcher in the Rye grudgingly; he thought it was overrated and probably right. I loved the book, having read it just months earlier - a sweet, civilizing story about a teenage outsider, and all the more attractive because objected to by adults (oh my God, it says fuck in there, even though the context is that Holden is trying to shield his younger sister Phoebe from seeing that; he's going to stand at the edge of the rye field, just by a cliff, and catch the kids before they hurtle over, the catcher in the rye). Brother thought the title was stupid, I think he actually said that. I countered that it's catchy. A wry comment, said he. The man was quick and had a good sense of humor. A sweet little book and it's probably had more staying power than Brother thought. Maybe at the level of the much assigned and equally charming Silas Marner, but unlike many others, Brother had the good sense to choose something we'd read and understand.

I was going to major in English in college and took the AP English test. It was a comedown getting a middling grade of 3 (my buddy Cliff nailed it with a 4 or 5). About the same time I scored in the high 700s on the math SAT, probably missed one or two questions - 800 is perfect. I figured destiny was giving me a tap on the shoulder and went on to get two degrees in math, which ended up being smart. I'd always been a reader, loved Beau Geste and Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea as a kid. One night I put the latter down right at the chapter The Attack of the Polyps - what's a polyp, a little shrimp or something. Only to find out the next night that we're talking giant squid, who engaged Captain Nemo and the Nautilus in an epic battle and came close to taking them down with them to the deep. It's been hard laying down a book showing any promise ever since. Sometime in junior year you start leaving that behind though, you want to read adult stories; I did anyway. And Brother Paul was right there to show us what the real thing looked like.

Mike Bertrand

December 15, 2013