Stalingrad

It is fitting to memorialize this epic battle today, the seventieth anniversary of its turning point. Throughout the summer and fall of 1942, the fascist hordes had thrown the Red Army back across to steppes, all the way to the banks of the mighty Volga. They had massacred their way through western Russia and the Ukraine, successfully continuing the blitzkrieg tactics resulting in the encirclement and near annihilation of multiple Soviet armies. Soviet propaganda then and subsequently put a stoic face on it all, but realistic accounts betray the sense of hopelessness and despair prevalent in the army as they saw their best and bravest cut down in unequal matches again and again, never ending it must have appeared at the time. The massed armor, air support, and superior organization and communications of the Wehrmacht seemed invincible.

It is fitting to memorialize this epic battle today, the seventieth anniversary of its turning point. Throughout the summer and fall of 1942, the fascist hordes had thrown the Red Army back across to steppes, all the way to the banks of the mighty Volga. They had massacred their way through western Russia and the Ukraine, successfully continuing the blitzkrieg tactics resulting in the encirclement and near annihilation of multiple Soviet armies. Soviet propaganda then and subsequently put a stoic face on it all, but realistic accounts betray the sense of hopelessness and despair prevalent in the army as they saw their best and bravest cut down in unequal matches again and again, never ending it must have appeared at the time. The massed armor, air support, and superior organization and communications of the Wehrmacht seemed invincible.

Something happened in the fall of 1942 that changed not only the outcome of a single battle, but the course of the Second World War and of 20th century history. The Red Army found a way to fight back in the streets and factories, before long the ruins, of Stalingrad. Stalin issued the order, "Not a Step Back!", he and Zhukov and other military leaders made the plans, the Soviet people and the Red Army executed those plans. A Red Army soldier in the ruins would cannily resist, stiffening the resolve of all who witnessed the act or heard about it. Think of Vasily Zaytsev, portrayed in the movie Enemy at the Gates, which misses details but absolutely captures the social and military essence of the rising fight-back.

This video from the Soviet point of view gives an idea of the brutality of the battle, including the difficulty of supplying the army from across the river when the Luftwaffe controlled the air - click the "Full screen" icon at the bottom right to show full screen. Fighting raged in streets, houses, factories, and ditches - many a spot changing hands numerous times throughout the battle. Women participated in great numbers as soldiers, medical workers, and in other frront-line positions. General Vasily Chuikov, the Red Army commander on the scene, makes a cameo appearance towards the end. His command post was only a few hundred yards from the Nazis throughout much of the battle; it was under high bluffs right up against the Volga and the Nazis once got close enough to send explosives down on a rope (soldiers higher up severed the rope to save their commanders).

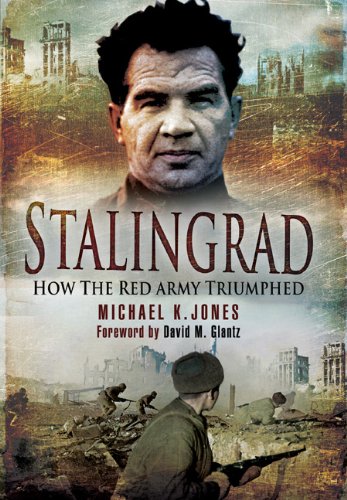

Chuikov, a hardened Communist and atheist, carried his mother's prayer card with him at all times. By some miracle, he survived the battle and became a high military leader in the Soviet Union after the war. Shortly before death, he asked to be buried on the Mamaev Kurgan, a central hill in Stalingrad where some of the bitterest and most sustained fighting had taken place. This account by one of Chuikov's officers from Michael Jones's recent book Stalingrad: How the Red Army Triumphed explains how he led and what it meant:

When Chuikov took command a guiding principle spread amongst us: there should no longer be a divide between commanders and ordinary soldiers. As a result, we shared our food together, and slept in the same trenches and dug outs. Battalion and even regimental commanders stayed in the line and fought with their men. Our rule became: every man is equal to another. It changed the mood amongst our soldiers. Once, when my men were overrun by the enemy, and small groups were fighting on in encirclement, Andryushenko (a higher officer) personally came with reinforcements and restored the situation. He fought his way through and rescued us. Actions like this created an atmosphere of extraordinary trust - and in return, no one wanted to let their commanders down.

Stalingrad was a fitting place for this showdown. Named after Stalin for his exploits in the vicinity during the civil war of the early twenties, the old city became an industrial powerhouse and showpiece during the Soviet period. Its massive factories had been retrofitted for war production, the same factories whose walls contained brutal mini-battles for months on end. Earlier in the season, before the Nazis penetrated the city limits, tanks drove off the production line unpainted, straight into battle. The Red October Factory, Pavlov's House, the Tractor Factory, the House of the Railway Workers, these are some of the places through which the battle seesawed for months.

The fighting ground on through September, October, November. There were many harrowing scenes where the enemy was on the verge of overrunning the entire city, only to be stopped by super-human effort and just enough resources delivered to just the right place at the right moment. It escaped the Germans that the balance in this war of attrition was slowly but decisively tipping away from them. The German Sixth Army was being ground down and losing its punch. The Soviet Stavka (central military council headed by Stalin) steadily and stealthily planned a massive counter-offensive involving over a million soldiers.

On November 19th the Red Army struck from north of the city, on November 21st from the south, with the object of surrounding the Sixth Army. The German flanks were weak and held down by allied forces, most Romanian. The Soviets made short work of them and their two groups met at Kalach behind Stalingrad on November 23rd. It had become bitterly cold all of a sudden; Wehrmacht equipment failed - they were outnumbered, outgunned, and out-hustled. In one incident, Russian mice had occupied the wiring compartments of German tanks and gnawed trough the wires, incapacitating an entire unit. The Red Army tightened the ring, rushing in reinforcements. Hitler forbade the Germans from attempting a breakout, the only possible way to save the situation. Even that possibility quickly became untenable, the supplies, morale, and military effectiveness of the Sixth Army degrading by the day. Leading Nazi Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe, promised resupply by air, a daunting task by any measure. It quickly became ridiculous as the Red Army started widening the ring and forcing longer flights; at one point, Soviet tanks literally rammed Luftwaffe planes sitting on a resupply air field as they overran it. As in other respects, Stalingrad turned the tide in the air, the Luftwaffe never again gaining the unchallenged supremacy they enjoyed as late as September 1942.

On November 19th the Red Army struck from north of the city, on November 21st from the south, with the object of surrounding the Sixth Army. The German flanks were weak and held down by allied forces, most Romanian. The Soviets made short work of them and their two groups met at Kalach behind Stalingrad on November 23rd. It had become bitterly cold all of a sudden; Wehrmacht equipment failed - they were outnumbered, outgunned, and out-hustled. In one incident, Russian mice had occupied the wiring compartments of German tanks and gnawed trough the wires, incapacitating an entire unit. The Red Army tightened the ring, rushing in reinforcements. Hitler forbade the Germans from attempting a breakout, the only possible way to save the situation. Even that possibility quickly became untenable, the supplies, morale, and military effectiveness of the Sixth Army degrading by the day. Leading Nazi Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe, promised resupply by air, a daunting task by any measure. It quickly became ridiculous as the Red Army started widening the ring and forcing longer flights; at one point, Soviet tanks literally rammed Luftwaffe planes sitting on a resupply air field as they overran it. As in other respects, Stalingrad turned the tide in the air, the Luftwaffe never again gaining the unchallenged supremacy they enjoyed as late as September 1942.

Some 300,000 soldiers were trapped, never to return to the fight. The pocket was reduced over a period of weeks and the last remnants surrendered on February 2, 1943. The German public was surprised and shocked by this reverse, the Soviet public less so. This was one of those great events in history whose significance almost everyone in the world understood at the time. The Russo-German war was by far the largest theater in World War II, perhaps 80% of the German war effort. It was inherently a war of attrition; the Germans could not replace those lost soldiers, the Soviets could and did. The Red Army regained its fighting spirit and learned how to win, how to combine air, armor, and infantry on mobile battlefields as the Germans had done so successfully. There was more hard fighting, much more, but everyone knew how this was going to end. On to Berlin!

The real story has been obscured, minimized and even falsified in the West for ideological reasons. Michael Jones retells the tale in a convincing and moving way (cover at top featuring Chuikov). One of his chapters is titled "An Army of Mass Heroism" and the phrase sticks, the valiance of Lyudnikov, Zholudev, Rodimtsev, Batyuk, and so many others almost beyond comprehension. They revived General Suvorov's old maxim, "Perish yourself but rescue your comrade!". Bravery, but also coolness under fire, oneness between officers and soldiers, and leadership from the front. Jones interviewed many Stalingrad veterans and is particularly compelling in explaining what really happened in the trenches. The Soviet people knew and the closer they were to it, the better they knew.

The real story has been obscured, minimized and even falsified in the West for ideological reasons. Michael Jones retells the tale in a convincing and moving way (cover at top featuring Chuikov). One of his chapters is titled "An Army of Mass Heroism" and the phrase sticks, the valiance of Lyudnikov, Zholudev, Rodimtsev, Batyuk, and so many others almost beyond comprehension. They revived General Suvorov's old maxim, "Perish yourself but rescue your comrade!". Bravery, but also coolness under fire, oneness between officers and soldiers, and leadership from the front. Jones interviewed many Stalingrad veterans and is particularly compelling in explaining what really happened in the trenches. The Soviet people knew and the closer they were to it, the better they knew.

Were there any question of bias in Jones's account, it is dispelled by the foreword of David M. Glantz, formerly a United States Army officer who served in Vietnam. Colonel Glantz was a historian for the army, and has become one of the leading authorities on the Russo-German war, specializing in research in the Soviet archives. Glantz says Jones's Stalingrad is "highly effective and utterly captivating ... the finest history of its type published to date".

Chuikov was tough and demanding and had a terrible temper, not always held in check. He exemplified as well as led the Red Army in this titanic struggle. His son Alexander recounted:

If he had just been a tough, abrasive, ruthless leader I think the battle would have had a different outcome. But crucially he also had a most unusual quality, a kind of warmth - a special empathy for ordinary soldiers and an ability to get really close to them. I will never forget one extraordinary incident, much later. We had been travelling by military train with my father - now Marshal of the Soviet Union - and made a short, unscheduled stop. My father was walking ahead of us with his adjutant when suddenly an almighty commotion broke loose. A circle of curious onlookers quickly gathered, with the adjutant flitting around in a state of total bewilderment.

Inside the circle I saw my father with a woman, totally overcome with emotion, her face streaming with tears, and I realized straightaway that she was a Stalingrad veteran. She kept repeating again and again, "Vasily Ivanovich, Vasily Ivanovich - God has sent you back to me!" They embraced each other - my father had also become very emotional and was crying as well. The surrounding crowd stood silent, absolutely mesmerized. Afterwards, I thought about that moment a lot, for the woman wanted nothing from my father - she was not trying to get any money or anything; she was just overjoyed to see him again. It was as if a curtain had briefly lifted, allowing me to glimpse the deep affection that had existed between the commander and his army. Later, I saw it again when veterans of Stalingrad visited my father's house. The thing that struck me most was the spontaneous warmth he evoked from ordinary people.

Mike Bertrand

November 23, 2012