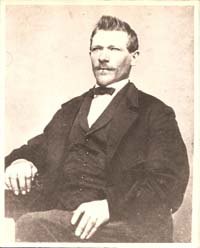

John Hidinger of the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

Sometimes mom talked about her grandfather's being in the Civil War and how he was captured and spent time in Confederate prisons. It was fascinating, especially considering that she was born and raised in Saskatchewan and was a naturalized American citizen. Her American roots are deep, going back to the founding of New Haven, Connecticut in the 1630s, but all that turned up later. Her grandfather John Hidinger was from Iowa, though born in Saxony and coming to the United States as a boy (the name was probably Heidinger in the old country). Imagine my surprise when rooting through the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society to find that he served with the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, the Eagle Regiment, so denoted because of their mascot, the eagle Old Abe, a sensation who occupied the Wisconsin state capitol for many years after the war, and whose replica overlooks the Wisconsin Assembly to this day. It tickled me as an anti-war protester on the University of Wisconsin campus circa 1970, because the right-wingers in the legislature would always call us out-of-town agitators. More like coming home I often thought when passing the Civil War cannon at Camp Randall where great-grandfather Hidinger trained, now a little park on the UW campus.

John Hidinger was born in Saxony on September 11, 1839 and grew up in the vicinity of Wadena, Fayette County, Iowa. He would have been 21 years old during the secession crisis in the spring of 1861 and one mystery is why he signed up in Wisconsin rather than with an Iowa unit. Both states were mobilizing furiously in the wake of the bombing of Fort Sumter. Maybe it was just convenient to join the La Crosse Rifles, the little group that ended up becoming Company I of the 8th Wisconsin, it isn't that far from Wadena. The muster roll shows that he signed up in La Crosse on September 3, 1861, a few days after his good friend and companion David H. Hall. It seems he was avoiding his parents' disapproval. Mom always said they left Germany in the 1840s to escape Prussian militarism and I've heard it in identical terms from third cousins in Iowa. They would not have been too happy about their eldest marching off to war so soon after escaping Europe to avoid that fate.

After returning from the war, John married Lydia Ann Walters on Christmas day, 1864 — she was eighteen years old. They had nine children from 1865 till 1883, six of whom themselves had children. John and Lydia's descendants have flourished in the United States and Canada. Gene Oliver did a genealogy in 1980, The John and Lydia Hidinger Family in America: 1846 to 1980[1], available in the Wisconsin Historical Society (I gave it to them!) and at that time there were 164 living descendants, a number that has no doubt increased. The family moved to the vicinity of Prescott, Adams County, IA in the southwestern part of the state sometime between 1873 and 1877.

The Civil War welded this country together; ante-bellum loyalty to individual states is hard to fathom today, but it was very real in 1860, fortified to be sure by the slave power's suspicion that the black Republicans (as they called them) would eventually take their slaves away. The states organized military units in the Civil War, that's why they're named the 8th Wisconsin or the 3rd Alabama. In union states, a regiment consisted initially of close to 1,000 soldiers broken into ten companies of about 100 (A to K, no J, at least for the 8th Wisconsin). The initial strength eroded over time, regiments in the field commonly being reduced to 600 effectives or less, and organization evolved and was regularized as the war went on; it's essential in reading accounts of battles and campaigns to have some understanding of how many men were in a regiment, brigade, division, and so on (excellent explanation here).

In his memoirs[2], General Grant well describes the cold fury felt by many sober people in the north as southern states started to secede after Lincoln was elected — how they dictated to the north for years, then used force to leave when losing one election; how they insulted the northern people as cowards and poltroons; how President Buchanan refused to take any defensive action as his Secretary of War dispersed federal forces and directed armaments to southern forts to be conveniently captured at the start of hostilities; how the southern grandees lorded it over their communities as if by divine right with little scope for democratic expression, supposed to be a hallmark of the American system.

The election was in November, Lincoln's inauguration in March under the old constitution, giving the secessionists ample time to organize as Buchanan looked on supine. Rage exploded throughout the north on April 12, 1861 when U. S. Fort Sumter was bombed, in Charleston harbor no less, the heart of secession. This is the environment John Hidinger found himself in, like so many others. Grant of course was a retired army officer, having seen service in the Mexican war. At this point he was a humble clerk in his father's store in Galena, Illinois, not far from Wadena or Madison. He describes how business took him to adjacent areas of Wisconsin and Iowa and how his opinion was sought out of an evening in these places once it was known he had been a captain in the regular army. His account of being pressed into service to organize Illinois regiments after Sumter, of directing the spontaneous mass enthusiasm into proper military channels, stands as a picture of what was happening throughout the north.

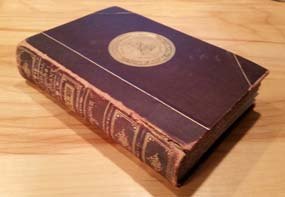

The definitive and near-contemporary account of the activities of the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, and all the other Wisconsin units, is E. B. Quiner's Military History of Wisconsin[3], published in 1866 and without question "prepared from the best material in reach" (p. 6):

The Eighth Regiment was organized at Camp Randall, Madison, and its muster into the United States service completed on the 13th of September, 1861, and on the 12th of October, it left the State for St. Louis.

So six weeks of basic training for John Hidinger before heading off to the field with the regiment, bullets flying in the vicinity by October 20. Mostly guard duty at first though, and engaged in April 1862 "in pursuit of the flying rebels after the evacuation of Island No. 10." That was a strategic point on the Mississippi River, a harbinger for the future — the 8th Wisconsin rarely found itself far from the great river throughout the entire conflict and was in fact attached to General John Pope's Army of the Mississippi during this early period. About the same time Grant opened up western Tennessee just to the east, driving down the Tennessee River (Forts Henry and Donelson, Feb 6-16, 1862; Shiloh, April 6-7, 1862), winning battles, capturing entire armies, and starting to cement his reputation.

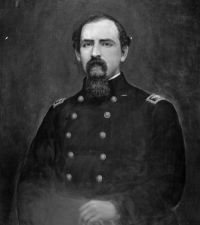

The 8th Wisconsin helped pursue the rebels into northern Mississippi after Shiloh, seeing real combat at Farmington, MS and Corinth, MS (a strategic railway junction) in May, 1862. Northern Mississippi quieted down for a while, then reignited in September and October, 1862 with battles at Corinth and Iuka and the 8th Wisconsin was in the thick of it. The rebels had a strongpoint at Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, commanding the river from high bluffs and impeding U. S. control of the river (New Orleans to the south had long since been occupied due to U. S. naval power). Grant's strategic goal in this period was to capture Vicksburg and open the Mississippi River to navigation, splitting the Confederacy. His first thought was to attack Vicksburg from the east and he assembled a massive supply depot at Holly Springs, MS, to forward this plan. He put Colonel Robert Murphy, formerly of the 8th Wisconsin, in charge of the depot, who promptly gave it up to the enemy without adequately preparing a defense and virtually without a fight. Writes General Grant:

On the 20th [of December, 1862] General Van Dorn appeared at Holly Springs, my secondary base of supplies, captured the garrison of 1,500 men commanded by Colonel Murphy, of the 8th Wisconsin regiment, and destroyed all our munitions of war, food and forage. The capture was a disgraceful one to the officer commanding but not to the troops under him. At the same time Forrest got on our line of railroad between Jackson. Tennessee, and Columbus, Kentucky, doing much damage to it. ... This demonstrated the impossibility of maintaining so long a line of road over which to draw supplies for an army moving in the enemy's country. I determined, therefore, to abandon my campaign into the interior ...

Still incensed twenty years later, Grant went on to accuse Murphy of gross cowardice if not disloyalty to the cause. He was cashiered and lucky not to be shot, having single-handedly undermined the entire strategy in the west. The 8th Wisconsin had campaigned in the vicinity and even visited Holly Springs according to Sgt. Ambrose Armitage of the 8th Wisconsin[4], but they were not part of Colonel Murphy's garrison when it was captured. Quiner has the 8th Wisconsin attached to Grant by March 1863 as he developed his fateful alternative Vicksburg strategy along the river.

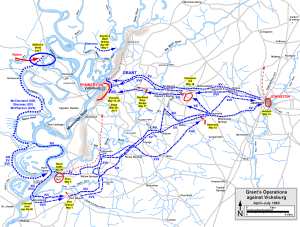

This was a decisive point in the war. Wikipedia has a great write-up on the Vicksburg campaign, including invaluable maps, but there is no better guide than Grant himself. He describes how the thicket of bayous on the east side of the river from Memphis all the way down to Vicksburg — the swampy Mississippi Delta region between the Mississippi, Tallahatchie, and Yazoo Rivers — made approach along that side of the river impossible short of the latitude of Vicksburg itself. He writes that in the wake of Holly Springs:

It was my judgement at the time that to make a backward movement as long as that from Vicksburg to Memphis, would be interpreted, by many of those yet full of hope for the preservation of the Union, as a defeat, and that the draft would be resisted, desertions ensue and the power to capture and punish deserters lost. There was nothing left to be done but to go forward to a decisive victory. This was in my mind from the moment I took command in person at Young's Point [just above Vicksburg on the west side of the river].

Grant and his soldiers worked feverishly on engineering projects along the Mississippi River in early 1863 to somehow bypass the strongpoint at Vicksburg and be able to run traffic down the river without being menaced by the guns on the heights. They dredged bayous, they built canals to divert the Mississippi, and tried other expedients, all to no avail. The 8th Wisconsin took part in these early feints, according to Quiner:

On [March] 29th, they proceeded down the river to Young's Point, near Vicksburg, where they engaged in fatigue duty, digging canal and building roads. The regiment was in Mower's brigade of Tuttle's Division of Sherman's Fifteenth Army Corps.

Grant mentions all three of these officers in his chapters on the campaign, Tuttle and his soldiers playing a critical role in capturing Jackson, MS in May 1863. In late April, Grant had the navy run transports and barges down the Mississippi, braving the guns. At the same time, he marched his vanguard down the west side of the Mississippi across makeshift roads and crossed the river early in the morning on April 30. Sherman, a trusted confidant, argued strongly against the move, pointing out that Grant was violating every axiom of war by abandoning supply lines. Grant told him that the nation could not sustain further dithering and it was time to go for broke:

When this was effected [the transport of the first units across the river] I felt a degree of relief scarcely ever equalled since. Vicksburg was not yet taken it is true, nor were its defenders demoralized by any of our previous moves. I was now in the enemy's country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.

He engaged in a campaign of movement against the larger enemy force in their own territory, defeating them piecemeal ("in detail" he says) in every battle. He feinted north to Vicksburg, then moved northeast to Jackson, captured with the help of John Hidinger on May 14 and slept that night in the bed occupied the night before by the rebel commander of the would-be relief force, Confederate General Joe Johnston. Sergeant Driggs of the 8th Wisconsin relates the capture of Jackson:

This was the 14th day of May, and a gala day for our troops. We were moving on cautiously and steadily through a heavy shower of rain towards the city of Jackson, the capital of Mississippi. [General] McPherson was fighting on our left. Met the enemy and drove him before us. The shells were bursting all around us, and the sharp crack of musketry mingled with the loud peals of thunder from the heavens, rendered this a most grand, sublime scene. Generals Sherman and Mower are riding rapidly by — orders come to charge bayonets — double quick! The army is in motion, our banners are unfurled to the breeze, and notwithstanding we have made a fatiguing march of some nine miles, over heavy roads, the men are eager for the affray. The enemy are falling back, and their artillery is less effective. With a rush and a yell that would have frightened the savages, our brigade went in upon them — charged the rebels across the fields, and at 3 p.m. captured the city of Jackson, all the enemy's artillery and a large amount of small arms and other valuable property. Our brigade went cheering up through the streets of the city on double quick, amid the wild huzzas of the victors, to the state capitol, where we took up our quarters — the enemy to the number of some eight thousand, under General Joe Johnston, having fled in a southerly direction. We tore down the rebel flag from the dome of the state house and placed our own proud banner there, where in triumph it floated during our stay in town.[5]

Grant and his soldiers pushed Johnston back, preventing any hope of relief from that direction, the only direction from which it could come. He entrusted Sherman ("Uncle Billy" to his soldiers) to destroy anything of military value in Jackson, including the railroad, which he did "most effectually". In a day or two, Sherman and XV Corps followed their comrades west to Vicksburg, participating in the valiant but unsuccessful assault on the city on May 22. They had literally come full circle, finally commanding the heights north of Vicksburg enabling them to resupply along the Yazoo River after three weeks hand-to-mouth, a blizzard campaign against a considerably larger foe, every battle won, the initiative retained at every turn. Grant remarks at one point that the enemy spent time and effort to cut off his supply line, a line that did not exist. This was Grant's great innovation, living off the land, and it shocked all his peers, friend and foe, never more than when witnessing its massive success. For individual soldiers and even patrols, foraging away from camp could result in contact with the enemy, never far away in his own land.

A seven week siege followed where the city was systematically hemmed in and cut off from all supplies, Sherman and XV Corps occupying the right wing to the north and northeast of the city. The lines were so close at points that open fraternization ensued, making clear the utter demoralization of the defenders by the end of June. Grant prepared to storm the city, confident of success, just at the point Confederate General John Pemberton surrendered on July 4. This was the second entire army Grant captured during the war, the first being at Fort Donelson, the third at Appomattox. The approach was a little more lenient than at Donelson, but not much ("No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately on your works", he had written the opposing general at Donelson). This decisive victory sealed the fate of the slave power. In General Grant's words:

The capture of Vicksburg, with its garrison, ordnance and ordnance stores, and the successful battles fought in reaching them, gave new spirit to the loyal people of the North. New hopes for the final success of the cause of the Union were inspired. The victory gained at Gettysburg, upon the same day, added to their hopes. Now the Mississippi River was entirely in the possession of the National troops; for the fall of Vicksburg gave us Port Hudson [the only remaining Confederate hold on the river] at once. The army of northern Virginia was driven out of Pennsylvania and forced back to about the same ground it occupied in 1861. The Army of the Tennessee united with the Army of the Gulf, dividing the Confederate States completely.

Grant's greatest friend through this and many another battle was President Lincoln, who wanted nothing more than the determined fighter Grant proved himself. Let the great one have the final word on Vicksburg:

The signs look better. The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea. Thanks to the great Northwest [now the midwest] for it. Nor yet wholly to them. Three hundred miles up, they met New England, Empire [New York], Key-stone [Pennsylvania], and Jersey, hewing their way right and left. The Sunny South too, in more colors than one, also lent a hand. On the spot, their part of the history was jotted down in black and white. The job was a great national one; and let none be banned who bore an honorable part in it. And while those who have cleared the great river may well be proud, even that is not all. It is hard to say that anything has been more bravely, and well done, than at Antietam, Murfreesboro, Gettysburg, and on many fields of lesser note. Nor must Uncle Sam's web-feet be forgotten [the navy!]. At all the watery margins they have been present. Not only on the deep sea, the broad bay, and the rapid river, but also up the narrow muddy bayou, and wherever the ground was a little damp, they have been, and made their tracks. Thanks to all. For the great republic — for the principle it lives by, and keeps alive — for man's vast future — thanks to all.

Keep in mind that the 8th Wisconsin was attached to Sherman's XV Corps during the Vicksburg campaign, so they participated in the battle of Jackson and the destructive work there subsequently, the march from Jackson to Vicksburg, the investment of the city, the assault of May 22, and the siege. That is, John Hidinger and the 8th Wisconsin fully participated in what was arguably the most crucial and successful campaign of the war.

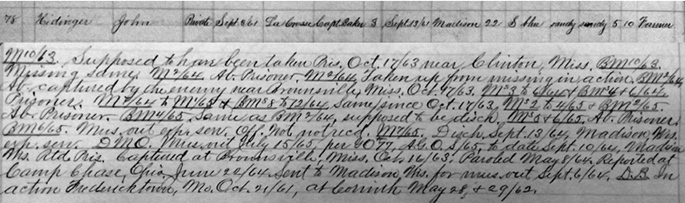

The 8th Wisconsin saw little to no action for several months, camping for some time near the Big Black River, the main natural impediment between Vicksburg and Jackson. They marched out on October 15, 1863 for a reconnaissance-in-force in a northeasterly direction. Sergeant Driggs reports that "at Brownsville, the second day out [Oct. 16] met a small force of rebel cavalry, and after a brisk little skirmish drove them pell-mell to and through the town, capturing a few prisoners." This was a momentous excursion for John Hidinger. His son Leroy Lemayne Hidinger tells the tale, as included in Gene Oliver's genealogy:

John Hidinger was living with his parents near Wadena, Iowa in the summer of 1861. His parents were opposed to the war and he was under age [ed: Hidinger was 22 years old when mustered in], so, when he decided to enlist in the Federal cause, he left Iowa and crossed over to La Crosse, Wisconsin and there enlisted in Company "I" of the 8th Wisconsin. He was continuously with the regiment until late in the year 1863 always as a private assigned to various duties. He served part of his time as a cook at Regimental Headquarters.

During the fall of 1863, while the regiment was located somewhere east of Vicksburg, Miss., he was captured by the Confederates. He had grown in favor at headquarters and been assigned to foraging supplies for the Colonel. He had gone beyond the lines into enemy territory, riding the Colonel's horse. While passing through some woods where the road had been cut through a little hill, he was suddenly ordered to halt. On glancing around he found that he was covered by the rifles of a number of the enemy and, being headed away from camp, decided not to run for it. He, therefore, surrendered.

There seems to be some confusion as to where he was captured. I had always understood he was captured near Holly Springs, Miss. The regiment was in that locality late in the year [ed: 1862] but Uncle Dave Hall has given careful consideration to the matter and is positive that he was captured during the absence of Uncle Dave on furlough, which was probably in September, 1863 while the regiment was still back of Vicksburg [ed: Hidinger was captured on Oct 17, 1863 near Brownsville, Miss.].

John Hidinger was sent with other captives to Belle Isle Prison at Richmond, Va. and spent part of his time in Belle Isle and part of his time in Libby Prison, the same city.

At the time of his capture he had two canteens. He had considerable paper money. While his captors were not looking, he rolled this money up and packed it into the older of the canteens. All of his personal effects were taken from him except he was permitted to retain the canteen with the money. After he had reached prison and was searched for the last time, he broke open the canteen and took out the money, placed it inside his clothing against his body to dry it out. Rations were scarce in Belle Isle and he would undoubtedly have died had he not had this extra money to purchase something to eat of the vendors who were permitted to enter the prison. Belle Isle Prison is an island in the James River, in the city of Richmond, Va. It is composed almost entirely of sand.

The prisoners obtained water by scooping out a hole in the sand until the water ran in. The surface of the island is only a few feet above ordinary water level and is covered by water at flood times. I have seen the island numerous times. It is now a storage area for old iron. Libby Prison is a short distance down the river and on the east side on high ground. It was a small prison and supposed to be for officers. There is now a grain elevator on the site where the prison once stood.

There is an amusing story told of the disappearance of a spotted dog that belonged to a Confederate Colonel who was in charge of Belle Isle Prison. The dog was well fed and fat. The prisoners were hungry. The dog frequently followed his master through the prison on inspection trips. One day the dog disappeared and that is the last the Colonel knew of him. As a matter of fact, several of the prisoners (one of whom was John Hidinger) caught the dog trailing behind his master, promptly choked him to death and buried him in a water hole in the sand. Four or five days later, after the furor and search for the dog had ceased, they dug him up and ate him and claimed that he tasted good.

John Hidinger was in Confederate prisons for nine months [ed: it was a little less than seven months] at which time he was paroled. He was a large man, about 6 feet [ed: Hidinger was 5'10" tall according to the Blue Book], weighed 200 lbs. or more in normal condition. When he left the prison he was so starved that he weighed only 95 lbs. and was unable to walk. He never fully regained his strength. He always suffered from stomach trouble and when working hard, found it necessary to have five meals a day. Uncle Dave Hall, referred to herein, was a buddy of John Hidinger until he was captured. Uncle Dave then went on through the war, staying with the regiment until it was disbanded at the close of the war.

On October 17, 1863 John Hidinger was reported missing the day after the engagement at Brownsville, a tiny village about twenty miles north west of Jackson. His fate was worse than the 30,000 Confederate prisoners Grant captured at the fall of Vicksburg, who were released. Hidinger became ill and was transferred to the hospital (deaths due to illness were rampant in both armies in the best of times). He was released ("paroled") on May 8, 1864 and returned to the north, mustering out at Madison on Sep 6, 1864. So almost seven months a prisoner-of-war, when he went through hell and almost died of starvation.

In his haunting story "The Return of a Private", the great Wisconsin populist writer Hamlin Garland writes of the return of a soldier from the La Cross Rifles to his farm:

A few years ago they had bought this farm, paying part, mortgaging the rest in the usual way. Edward Smith was a man of terrible energy. He worked "nights and Sundays," as the saying goes, to clear the farm of its brush and of its insatiate mortgage! In the midst of his Herculean struggle came the call for volunteers, and with the grim and unselfish devotion to his country which made the Eagle Brigade able to "whip its weight in wildcats," he threw down his scythe and grub-axe, turned his cattle loose, and became a blue-coated cog in a vast machine for killing men, and not thistles. While the millionaire sent his money to England for safekeeping, this man, with his girl-wife and three babies, left them on a mortgaged farm, and went away to fight for an idea. It was foolish, but it was sublime for all that.

John married Lydia Ann Walters on Christmas day 1864, soon after returning home. She had just turned eighteen, namesake for my mother and daughter. John Hidinger and his associates put down the slave power once and for all and saved the republic. American and world history would have unfolded very much differently had the story ended otherwise. Differently and worse for all of us.

Madison, WI

Sep 13, 2017

PS: John and Lydia Hidinger have some 200 living descendants and I'd be glad to hear from any of you (click my name immediately above to send an eMail).

^ 1. The John and Lydia Hidinger Family in America: 1846 to 1980, by Frederick Eugene Oliver (1980).

^ 2. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, by Ulysses S. Grant (Charles L. Webster and Company, 1885).

^ 3. Military History of Wisconsin, by E. B. Quiner (Clarke and Company, Publishers, 1866).

^ 4. Brother to the Eagle: The Civil War Journal of Sgt. Ambrose Armitage, 8th Wisconsin Infantry, edited and annotated by Alden R. Carter (Booklocker.com, Inc., 2006), ISBN 978-1-60145-042-5. Visited Holly Springs: p 197.

^ 5. Opening the Mississippi; or Two Years' Campaigning in the South-West, by George W. Driggs (Wm. J. Park & Co., Madison, 1864). Driggs was a Sergeant-Major of the 8th Wisconsin.